A major re-write?

If journalism is the first draft of history, I may have to go for a major re-write. How much can the draft "Reform Treaty" be changed at an inter-governmental conference, which opens in July? The Germans told us for weeks that an agreement at last week’s summit would only be worthwhile if it was very, very clear. If all the major political points, and indeed the minor ones, were dealt with. They said that the civil servants would just be left with pulling the thing together and sorting out a few legal niceties. Every other government agrees with them. I certainly believed them. You might think this naive, but opponents of the treaty also argue that what it means is clear enough to demand a referendum.

So a couple of days ago I said that a senior academic was “plain wrong”, according to everyone I had talked to, when he argued in an interview that no-one could yet say what the treaty meant. I didn’t name him at the time, but he is Professor Damian Chalmers, of the London School of Economics, and he wrote to me very politely making a powerful case so I asked him if he could put his view here:

- "Visitors from Mars would look at the current state of play on the Reform Treaty with some bemusement. This group of European States, having come together ostensibly to produce the richest and most progressive region in the world, cannot even produce a document that anybody can understand or summarise. Is it significant enough for a referendum? What does it change? Nobody is quite sure. So-called experts come out with statements that appear empty, contradictory and arcane. If the visitor were a policeman, the words 'piss up' and 'brewery' might be mentioned. If they were a little green monster, they might take a bit of chewing gum and pop off in their space ship back home.

- There is a simple reason why this is so. The heads of state are intelligent people aided by intelligent people. If they had wanted a clear, comprehensive document, they would have written one. It is neither clear nor comprehensive because they did not want it to be these things.

- How do we know this?

- First, there is the length. The length is 16 pages, and a fair part of this is empty page or waffle. The constitutional treaty agreed in 2004 is 482 pages long. The agreement, whilst it refers a lot to the constitutional treaty, is not intended to be, nor could it be at that length, a comprehensive resettlement of the latter.

- Secondly, there is the format. Normally, six months before an agreement (the current time-frame) one would have a framework document. This takes the form of a legal text with square brackets surrounding the points still to be agreed. There is no such detailed roadmap this time. Instead, the 16 pages contain a mixture of declarations ('No constitutional status for the Reform Treaty'); legal texts (the protocols with the UK opt-ins and outs); and instructions. Many of these instructions are vague, incomplete and even contradictory.

- Finally, civil servants say getting a final text by December will be a big ask, which would be odd if they only had to dot the i's.

- We also know why this is so. The Germans wanted to bring the matter to a head, after two years. Except there was a problem. Two-thirds of the member states had ratified the constitutional treaty and had indicated that the new treaty should be the same, with a few concessions for the individual trouble-makers. The other one-third did not see it this way. They not only had their individual red lines but thought the new treaty should be more modest in tone and substance than the old one. Otherwise, they would threaten a referendum.

How to bridge the gap? Here Angela Merkel played a blinder. The agreement states that the constitutional treaty will only be included in the Reform Treaty 'as specified in this mandate'. The one-third will argue the constitutional treaty matters only insofar as there are references to it in the document, and the rest is up for negotiation (as Geoff Hoon did on Newsnight). As the agreement is incomplete and only makes sense by looking at the constitutional treaty, others will argue that what has been agreed is, more or less, the constitutional treaty (the argument of the Irish government).

How to bridge the gap? Here Angela Merkel played a blinder. The agreement states that the constitutional treaty will only be included in the Reform Treaty 'as specified in this mandate'. The one-third will argue the constitutional treaty matters only insofar as there are references to it in the document, and the rest is up for negotiation (as Geoff Hoon did on Newsnight). As the agreement is incomplete and only makes sense by looking at the constitutional treaty, others will argue that what has been agreed is, more or less, the constitutional treaty (the argument of the Irish government).- Last week was significant and gave many important and detailed markers, but it has also allowed a lot of room for negotiation. In terms of giving the citizen a clear idea of what is going on, forget it!

- Let us take the The Charter of Fundamental Rights, a hot issue for the UK.

- The bottom line for citizens is whether UK laws can be struck down for violating European Union fundamental rights and when this can take place.

- Well, the reality is that since 1990 national laws in quite wide areas of activity have been subject to European Union fundamental rights law. Only last December, for example, the UK was found to have violated them for designating an organisation a terrorist organisation. The charter is only one source amongst many of these fundamental right laws. Others include international human rights treaties and national constitutional traditions all of which are synthesised by the European Court of Justice to generate its interpretation of a European fundamental right.

- When do these laws apply? The remit of these fundamental rights laws seem to be extended by the latest agreement to cover national measures involving policing and judicial co-operation in criminal matters, as these policies are now to be treated in the same manner to other policies. This would be a significant extension, although the agreement does make clear that national security is the sole responsibility of member states.

- So would the UK be subject to this – the extension of the remit of fundamental rights laws to policing and judicial co-operation in criminal matters - and to the Charter of Fundamental Rights? Well, we have an opt-out from the charter but not other fundamental rights norms... and here is the catch, all the charter claims to do is 'confirm' these other fundamental rights norms. It would be open to any court to find a violation of both sets of norms - and a violation of one would entail a violation of the other - and so the UK would still get caught. But this goes against the spirit of the opt-out, so maybe not...

- But what about the opt-in to police and judicial co-operation in criminal matters, does it not protect us? It is true we will not participate in future legislation in these fields unless we wish. We are bound, however, by existing laws and decisions of the existing bodies (eg Europol and Eurojust). Moreover, in relation to EU fundamental rights, these bind member states when they are acting within the field of EU law. Even if we have decided not to opt in to legislation here, we are still operating within this field (of police co-operation and judicial co-operation in criminal matters) and are therefore potentially bound by EU fundamental rights norms.

- And one final spanner to throw in the works. The EU established a Fundamental Rights agency earlier this year to check EU legislative proposals are compatible with, among other things, the Charter of Fundamental Rights. Will the UK be bound by it insofar as its rulings on the charter affect EU legislation applicable in the UK?

- Confused? There will also be a few civil servants scratching their heads..."

So is the cat alive or dead? Will we really not find out until October? And I do promise to start writing about something else soon. Possibly. I think I am turning into one of those people others steer clear of in the corridors of Westminster.

Most Conservatives will vote for their party policy. The position of the Lib Dems is officially undecided. Many are pretty keen on the idea of letting people vote on individual subjects. Others have seats in the Eurosceptic south west. So, the party just could decide to back a referendum vote, as it did last time. I notice that three Labour MPs have demanded a referendum. That is still rather short of the rebellion of 80-odd Labour members the amendment would need to succeed. But it would all turn the heat up under Mr Brown. Which leads me to the only real reason he'd give in - to lessen the risk of being sacked by the British people in a general election.

Most Conservatives will vote for their party policy. The position of the Lib Dems is officially undecided. Many are pretty keen on the idea of letting people vote on individual subjects. Others have seats in the Eurosceptic south west. So, the party just could decide to back a referendum vote, as it did last time. I notice that three Labour MPs have demanded a referendum. That is still rather short of the rebellion of 80-odd Labour members the amendment would need to succeed. But it would all turn the heat up under Mr Brown. Which leads me to the only real reason he'd give in - to lessen the risk of being sacked by the British people in a general election. Politicians all over Europe are worried about nextdoor's dominos. One of the reasons that it was so difficult for Tony Blair to resist the referendum call was that President Chirac had unhelpfully changed his mind and offered the French people one. Remember how the No-vote in Denmark over the Maastricht treaty rocked British politics? It didn't provoke a referendum but it did strengthen the hand of the Eurosceptics and led to the slow and agonising dismemberment of John Major's authority.

Politicians all over Europe are worried about nextdoor's dominos. One of the reasons that it was so difficult for Tony Blair to resist the referendum call was that President Chirac had unhelpfully changed his mind and offered the French people one. Remember how the No-vote in Denmark over the Maastricht treaty rocked British politics? It didn't provoke a referendum but it did strengthen the hand of the Eurosceptics and led to the slow and agonising dismemberment of John Major's authority.  The Netherlands is a different matter. The Socialist Dutch MP Harry Van Bommel told me that the treaty was "the constitution in drag", and trying to pretend otherwise was "absolutely unworthy" of the prime minister. A debate is going on in The Hague as I write. The Dutch government clearly does not want a referendum but there might be one small problem. The coalition government took ages to form and is a very fragile thing. It includes three members of the

The Netherlands is a different matter. The Socialist Dutch MP Harry Van Bommel told me that the treaty was "the constitution in drag", and trying to pretend otherwise was "absolutely unworthy" of the prime minister. A debate is going on in The Hague as I write. The Dutch government clearly does not want a referendum but there might be one small problem. The coalition government took ages to form and is a very fragile thing. It includes three members of the  Of course, the opposition’s ammo hasn’t all been stolen. William Hague issued a statement well before the ink was dry, saying that what we had all seen by then amounted to a major transfer of power. Tony Blair has agreed to give up its veto in more than 40 areas, all of them minor according to the government. Some argue that having a President of the European Council could lead eventually to a directly-elected President of Europe. The European Union gains a single legal personality, in other words the right to join international organisations.

Of course, the opposition’s ammo hasn’t all been stolen. William Hague issued a statement well before the ink was dry, saying that what we had all seen by then amounted to a major transfer of power. Tony Blair has agreed to give up its veto in more than 40 areas, all of them minor according to the government. Some argue that having a President of the European Council could lead eventually to a directly-elected President of Europe. The European Union gains a single legal personality, in other words the right to join international organisations. The Javier Solana role stays as High Representative (rather than Foreign Minister, as the constitution proposed).

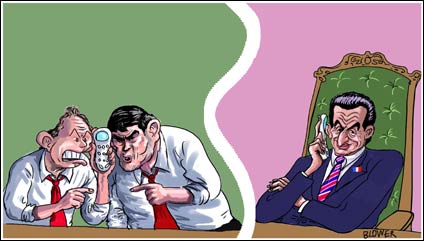

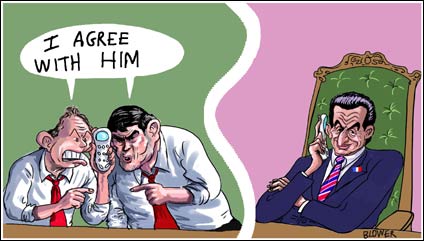

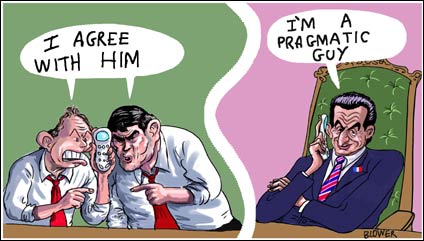

The Javier Solana role stays as High Representative (rather than Foreign Minister, as the constitution proposed). After Sarkozy’s triumph, I am sure the European Commission and Tony Blair were in a bind. Very close to a deal, focused on the red lines, they didn't want to object to something that hits them out of the blue.

After Sarkozy’s triumph, I am sure the European Commission and Tony Blair were in a bind. Very close to a deal, focused on the red lines, they didn't want to object to something that hits them out of the blue. The first rests on the premise that many French people voted "No" because of fears of globalisation, and a belief that Brussels was on the side of big business and Anglo-Saxon economics. You wouldn't know it from reading the British papers, but that is how many on the continent see it. So this could be a presentation sop, so Mr Sarkozy can say, a la Blair, all the nasty bits of the constitution have gone.

The first rests on the premise that many French people voted "No" because of fears of globalisation, and a belief that Brussels was on the side of big business and Anglo-Saxon economics. You wouldn't know it from reading the British papers, but that is how many on the continent see it. So this could be a presentation sop, so Mr Sarkozy can say, a la Blair, all the nasty bits of the constitution have gone.

A lot is at stake. While European leaders waver between predicting a crisis if there’s failure and the admission that life would go on, it is very clear that it will be seen by many as a monumental failure if there is no agreement. It would almost amount to a humiliation for Germany’s chancellor, Angela Merkel. And for the new boy, President Sarkozy of France, failure would be almost as bad. Allies of Tony Blair say that’s why it’s right that he, not Gordon Brown, negotiates. He can make the most of his personal relationship with those two leaders and take the hits on Gordon’s behalf. And, yes, they have been speaking nearly every day about this summit.

A lot is at stake. While European leaders waver between predicting a crisis if there’s failure and the admission that life would go on, it is very clear that it will be seen by many as a monumental failure if there is no agreement. It would almost amount to a humiliation for Germany’s chancellor, Angela Merkel. And for the new boy, President Sarkozy of France, failure would be almost as bad. Allies of Tony Blair say that’s why it’s right that he, not Gordon Brown, negotiates. He can make the most of his personal relationship with those two leaders and take the hits on Gordon’s behalf. And, yes, they have been speaking nearly every day about this summit.  Mr Blair intends to be a great deal more forthright. He is unapologetic that his problem is with the home front. It’s one of the reasons he wanted to negotiate at this summit, rather than hand over to Gordon. He will tell his counterparts from other countries that, yes he signed it two years ago but there’s no point agreeing to something if the government is going to be forced into a referendum. It would mean another two years of uncertainty, and if the referendum was lost Europe would be back at square one in 24 months’ time, with some saying they had to start all over again. His message will be: “Look guys, do you want a deal or not?” There is no point in him agreeing to anything that comes in beneath the bar he has set up.

Mr Blair intends to be a great deal more forthright. He is unapologetic that his problem is with the home front. It’s one of the reasons he wanted to negotiate at this summit, rather than hand over to Gordon. He will tell his counterparts from other countries that, yes he signed it two years ago but there’s no point agreeing to something if the government is going to be forced into a referendum. It would mean another two years of uncertainty, and if the referendum was lost Europe would be back at square one in 24 months’ time, with some saying they had to start all over again. His message will be: “Look guys, do you want a deal or not?” There is no point in him agreeing to anything that comes in beneath the bar he has set up.

Well, it’s the summer and in the summer, we have to go a warehouse with attached padded cell (if we can find a picture you’ll see what I mean) in the one bit of Luxembourg that’s grey, horrible and has more roundabouts than Milton Keynes. Because of an agreement made in the dawn of time to help out Luxembourg, one of the poorest counties in the EU. Oops my mistake it’s the richest isn’t it? Excuse my bile. Oh well, a two-and-a-half-hour drive on a Sunday rather than four stops on the metro. This is what people call a “jolly”. I’d rather have a few more hours with the family.

Well, it’s the summer and in the summer, we have to go a warehouse with attached padded cell (if we can find a picture you’ll see what I mean) in the one bit of Luxembourg that’s grey, horrible and has more roundabouts than Milton Keynes. Because of an agreement made in the dawn of time to help out Luxembourg, one of the poorest counties in the EU. Oops my mistake it’s the richest isn’t it? Excuse my bile. Oh well, a two-and-a-half-hour drive on a Sunday rather than four stops on the metro. This is what people call a “jolly”. I’d rather have a few more hours with the family. First off, I am watching an exercise, not a real operation. Secondly,

First off, I am watching an exercise, not a real operation. Secondly,  Veteran Eurosceptic Lord Pearson,

Veteran Eurosceptic Lord Pearson,  Back at the news conference, people feel the question “Does it undermine Nato?” hasn’t been answered. Mr Solana jumps in: “I will take that question. There is no question of competition but a division of labour, which is necessary with the number of crises we have. The needs are many and the resources are limited.”

Back at the news conference, people feel the question “Does it undermine Nato?” hasn’t been answered. Mr Solana jumps in: “I will take that question. There is no question of competition but a division of labour, which is necessary with the number of crises we have. The needs are many and the resources are limited.” When the French and the Dutch voted against

When the French and the Dutch voted against  But watch out for Poland. They want to change the voting system proposed in the constitution and to return to a system proposed under the

But watch out for Poland. They want to change the voting system proposed in the constitution and to return to a system proposed under the  I've been the BBC's Europe editor since the autumn of 2005. Before I had been working for the BBC at Westminster for ooh, I thought it must have been at least 10 years. When I came to do the sums I had been covering British politics for 17 years. How time flies when you're enjoying yourself.

I've been the BBC's Europe editor since the autumn of 2005. Before I had been working for the BBC at Westminster for ooh, I thought it must have been at least 10 years. When I came to do the sums I had been covering British politics for 17 years. How time flies when you're enjoying yourself.  I live in Brussels with my wife and three children. The fox got the rabbits, the cats died sometime ago but the teenager has a couple of rats. I like cooking, eating, reading and sleeping. These have never let me down: Lee Perry, Joe Strummer (except by dying), Massive Attack, Thievery Corporation, Iain M Banks, Phillip Roth, Haruki Murakami, Michel Faber.

I live in Brussels with my wife and three children. The fox got the rabbits, the cats died sometime ago but the teenager has a couple of rats. I like cooking, eating, reading and sleeping. These have never let me down: Lee Perry, Joe Strummer (except by dying), Massive Attack, Thievery Corporation, Iain M Banks, Phillip Roth, Haruki Murakami, Michel Faber. I’m Mark Mardell, the BBC's North America editor. These are my reflections on American politics, some thoughts on being a Brit living in the USA, and who knows what else? My

I’m Mark Mardell, the BBC's North America editor. These are my reflections on American politics, some thoughts on being a Brit living in the USA, and who knows what else? My