What is web science?

- 11 Mar 08, 17:40 GMT

In the august surroundings of the Royal Society of Arts and Sciences, in a lecture theatre decorated with 18th Century paintings, a crowd gathered on Tuesday morning to celebrate the birth of a new science.

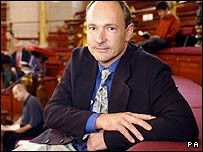

It’s called Web Science, and is an attempt to start understanding and exploring the ever growing phenomenon of the world wide web. Who better, then, to be the main speaker at today’s event than Sir Tim Berners-Lee, the inventor of the web?

Sir Tim began with a vivid picture of the way his baby has grown: “There are more pages out there on the web than there are neurons in your brain.” He went on to explain that he hadn’t been sure about using the word “science” in this new discipline because web science needed to reach out and include sociologists, philosophers and artists as well as the technical community.

“When we build the web,” he explained, “we choose a lot of the answers to philosophical questions. We are constructing a whole new world and we are writing down the rules. And a huge amount of the design involves the psychology of the user.” As an example he described how e-mail had taken off because users trusted each other to send only valuable material – but was now under threat because of spam: “The social assumptions have changed – people no longer assume that messages they are getting are messages they need.”

Sir Tim is working with the Southampton University computing science department, which along with Boston’s MIT, is leading the Web Science Research Initiative.

Sir Tim is working with the Southampton University computing science department, which along with Boston’s MIT, is leading the Web Science Research Initiative.

Professor Wendy Hall from Southampton (you can see an interview with her above) explained. “The web is the elephant in the room – it has transformed our lives, but we never see it. We feel the time has come to study it – to see its benefits and understand its possible dis-benefits.”

Her colleague Professor Nigel Shadbolt sketched out some early projects to illustrate the areas the new science might investigate. He showed a map of the blogosphere - "it's a butterfly shape" - which illustrated the way communities coalesce around certain blogs. He showed why research into Wikipedia needed a sociological angle – what drives the users to write entries? – As well as technical analysis of the patterns of its growth.

Professor Shadbolt also gave some insights into the semantic web – a project which Tim Berners-Lee and the Southampton University academics have been pursuing for some time, to a degree of scepticism from other parts of the web community. He described plans to give every fact on the internet its own web address, with the aim of building a “data web” where every connection was more clear and more searchable. “So you could ask questions like show me all the tennis players in Moscow,” he explained.

Of course, scientists have been examining the web for some time. Now, though, they are trying to work out how they can guide its future growth. Tim Berners-Lee puts it like this: “The web is basically a web of people. Because it’s something we created, we have a duty to make it better.”

But the web has grown and prospered without any real guiding hand, despite the attempts of governments and businesses to bend it to their will. So can the web scientists really do anything to shape its future?

The BBC is not responsible for the content of external internet sites