Observing ice crystals

d ~ 241'843'200 km: day 94

In my previous post I mentioned that clouds of snow crystals are above us all year round, thousands of metres above us in the atmosphere. In this post I want to show you how we can continuously observe these ice crystal clouds using radar. Radar works by transmitting a short burst of radio waves (a 'pulse'), then listening to see if part of that pulse is reflected back. By timing how long it takes for the reflections to come back to the radar, we can work out how far away the reflecting object is. Most people are probably more familiar with radar being used to detect aircraft. But just as aircraft reflect radio waves, so too do snowflakes - the only difference is that the reflections are a lot weaker.

So if we want to monitor snow crystals above us, we need a sensitive radar. Fortunately the UK has one of the best facilities for this in the world: the Chilbolton Observatory in Hampshire. Founded in the 1960s for radio astronomy work, since then a number of different radars, remote sensing and meteorological instruments have been installed there making it perfect for cloud and precipitation research. Crucially, a significant number of instruments are now operated 24 hours a day, 365 days a year, letting us continuously monitor the properties of clouds. Here's an example of a cirrus cloud:

(c) Chris Westbrook

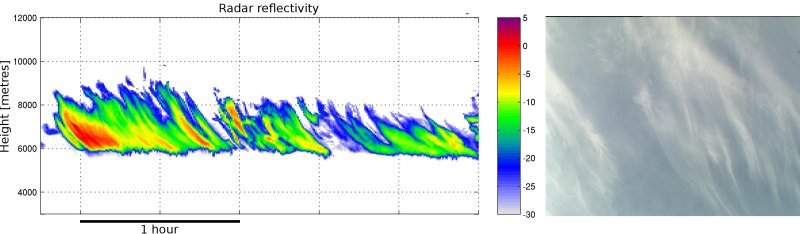

On the left here you can see the signal we measured using our 'Copernicus' cloud radar - the colours are the reflections from the snow crystals. The warmer the colours, the bigger the crystals are. On the right you can see a photograph taken by an automated sky camera - this is what the same cloud looks like to the naked eye. In spite of how tenuous the cloud looks in the photograph, the radar demonstrates this is a big mass of ice: the cloud is 3km (just under 2 miles) deep. The streaky character of the cloud is very obvious in both images - this is caused as ice particles are formed initially in narrow regions where the air is rising near the top of the cloud. The crystals then grow, and fall, and as they do so they form these streaks. The streaks are curved because the wind is strong up at 8000 metres, and this blows them off-course as they fall.

We can measure how fast the crystals fall by making use of the 'Doppler effect' where the reflected pulse is shifted in frequency (this is the same as when a police car siren is high pitched coming towards you and lower pitched as it goes away from you). In this case the crystals were falling at about 1m/s, so it would have taken them a bit less than an hour to fall from top to bottom of the cloud. You'll see when they get to 6000m the crystals seem to disappear. This is because the air beneath is too dry, and the crystals evaporate before they get anywhere near the ground. This saga goes on all the time above our heads when there is cirrus around, it is incredible. Cirrus clouds actually warm the planet slightly (a greenhouse effect), and because they are so common across the globe, it is very important to understand how they work so we can get them right in climate models.

The second kind of cloud I'd like to show you is another common one - but one which we are now discovering is much more common than was previously thought. These clouds contain 'supercooled' water droplets. Amazingly these water droplets do not freeze, even at temperatures far below 0 degrees C. Because the droplets themselves are so minute (1/10th the width of a human hair) normal radar can barely detect them. But if we exploit a different kind of radar, which uses infrared light rather than radio waves, we can see exactly where these droplets are. It's called 'lidar'. Here's an example from back in December last year when things were very chilly and we were getting some snow:

(c) Chris Westbrook

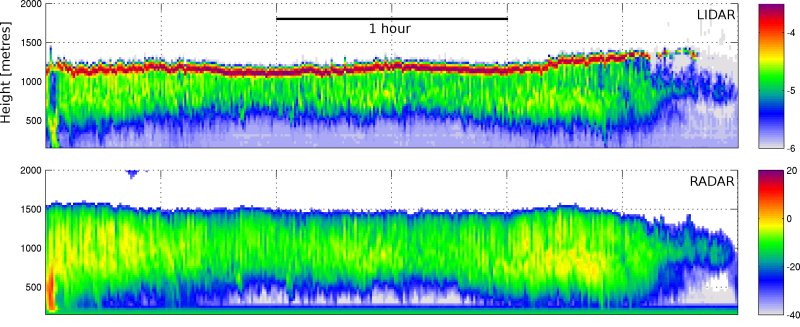

The top picture is the lidar - you can see that red stripe at the top of the cloud - that's the supercooled water - it's really reflective to infrared light. The green stuff faling underneath is snow crystals, formed as some of the droplets freeze. The bottom picture shows the radar image - this just detects the snow crystals. The top of this cloud is -13 degrees C, and it's amazing that the liquid can be this cold without all freezing. Actually our work has shown that even as cold as -25C, around half the snow crystal clouds in the atmosphere have supercooled water at the top of them! Exactly how this water persists at top of these cold clouds is still not clear: even though the droplets do not all freeze, the presence of other ice crystals around them should in theory make them evaporate - but they don't. This is important, because the droplets reflect a lot of sunlight (just the same as they do to our lidar pulse), cooling the planet.

That's a small sample of some of the things we can observe at Chilbolton. If you want to see what's above your head right now, check out the realtime images.

Kate Humble:

Kate Humble: Helen Czerski:

Helen Czerski: Stephen Marsh:

Stephen Marsh: Aira Idris:

Aira Idris:

Comments Post your comment