Doctors, scientists, nurses, care staff, and countless other professionals across the globe are putting their all right now into keeping us safe.

But while their work is of the absolute essence at this crucial time in history, this is something they’ve been doing as long as their jobs have existed.

We shine a light on three women from past and present whose work is helping us to tackle covid-19.

Sophia Louisa Jex-Blake

While during the first lockdown in 2020 NHS and caring staff were getting weekly rounds of applause across the country, in the 1800s women were getting heckled for merely trying to study medicine.

In 1870 at the University of Edinburgh, Sophia Louisa Jex-Blake and six other women (Isabel Thorne, Edith Pechey, Matilda Chaplin, Helen Evans, Mary Anderson Marshall and Emily Bovel) became known as the Edinburgh Seven. On the way to classes, they were shouted at by members of the public and had the gates to the university slammed in their faces. Their crime? Trying to go to a medical lecture.

While they passed the exam to be there and study, they were blocked from graduating and obtaining their medical licences. Not to be defeated, Sophia went on to earn a medical degree from the University of Bern in Switzerland and was eventually granted a licence to practice by the King’s and Queen’s College of Physicians, Dublin.

She became the first practising female doctor in Scotland, and one of the first in England, Wales and Northern Ireland (the first was a woman named Elizabeth Garrett Anderson who obtained her licence in England in 1865).

Women weren’t officially allowed to become doctors until the Medical Act was passed in 1876, something Sophia personally campaigned for. Because of her efforts, and those of other female medical students in that time, women in the UK are freely allowed to study medicine and are today fighting coronavirus on the front lines of the pandemic.

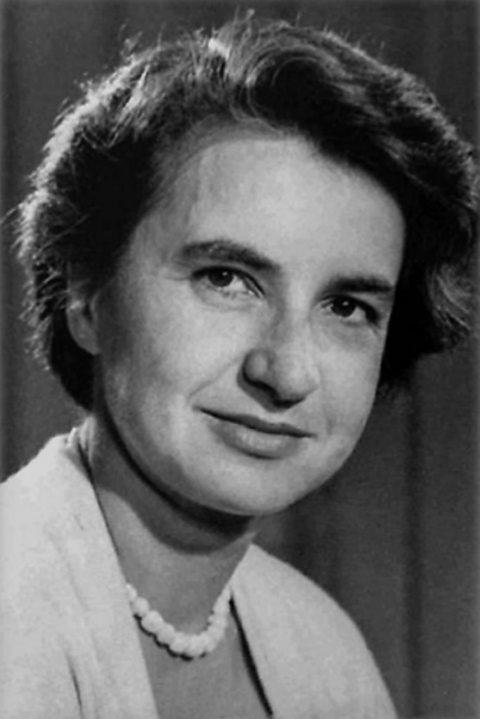

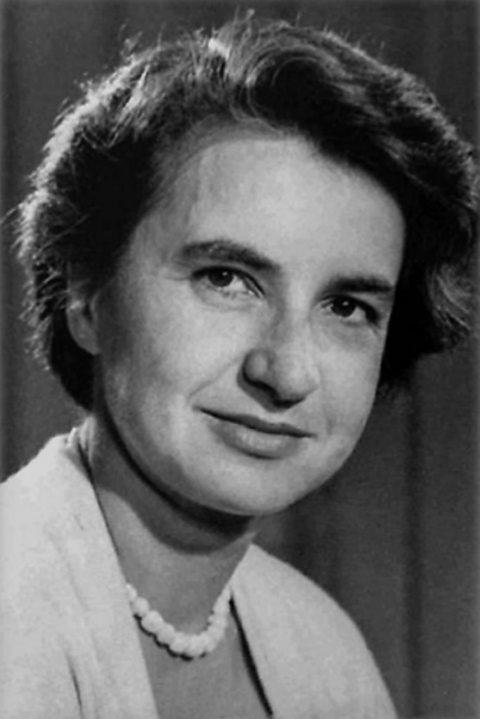

Rosalind Franklin

It wasn’t smooth sailing for female medical professionals from there on, however. Rosalind Franklin was instrumental in discovering the double helix structure of DNA - she used a method called x-ray crystallography to photograph it which showed the world exactly what it looked like for the first time.

However, she missed out on a Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, which was awarded to her three male colleagues in 1962: James Watson, Francis Crick, and Maurice Wilkins. This is because she sadly died of ovarian cancer in 1958, before the prize was awarded, and they’re not given posthumously. But until recently, Rosalind and her huge contribution hardly received the credit they deserve.

You might be wondering why her discovery is important in the fight against the pandemic, though. Well, Rosalind Franklin didn’t stop at studying DNA, the building blocks of human beings. She also researched viruses and saw that they have a similar (yet single-stranded) structure called RNA, which makes up their genetic code.

If you’re wondering why RNA rings bells, it’s because this is what scientists look for when testing for coronavirus cases. The swab you put in your throat and up your nose when you take a test is used to see if any RNA material matching that of the coronavirus is present in your body. Two of the approved Covid vaccines were also developed using a synthetic version of some of the virus’s messenger RNA.

Kizzmekia Corbett

This knowledge of viruses’ RNA is invaluable in helping doctors and scientists tackle coronavirus right this very second, such as Kizzmekia Corbett. She isn’t a female scientist from history - she’s a female scientist making history as we speak.

She’s a viral immunologist and research fellow who has been leading a team researching various coronaviruses for five years. She’s also the co-lead of a team that developed the American Moderna vaccine.

The explanation she gave on American news programme 'CBS This Morning: Saturday' of how this particular vaccine works was as follows: "The vaccine teaches the body how to fend off a virus, because it teaches the body how to look for the virus by basically just showing the body the spike protein of the virus. The body then says 'Oh, we've seen this protein before. Let's go fight against it.'”

The work she’s doing isn’t just a professional milestone, but something that she’s proud of on a very personal level. She recently said in an interview with Essence in the US that black people in America are about two to three times more likely to die from covid-19, so “as a black woman… it’s extremely important me to have made that history from a scientific perspective”.

Coronavirus: How I'm coping being away from loved ones

Tips on how to deal with being away from friends and family.

Fabulous scientific facts - chosen by scientists

The finest undersea teamwork, metallic rain and the fish that could help us reach Mars

Ten amazing scientific and technological breakthroughs of the 2010s

From lab-grown burgers to water on Mars.