On 8 November 1895, German scientist Wilhem Röntgen discovered x-rays – a new technology that revolutionised medicine.

Only, the interesting thing is, he didn’t actually mean to.

Röntgen’s discovery was entirely accidental as one of a number of accomplishments or inventions that worked out well, even if they didn’t go as originally planned.

BBC Bitesize takes a look at some of the happy accidents that went on to change the world.

X-Ray

Röntgen was originally trying to find out whether cathode light rays - invisible streams of electrons, that could only be seen in glass vacuum tubes - could actually pass through the glass.

While working in his Wurzburg laboratory, in the Bavaria region of Germany, he noticed a glow projecting onto a nearby screen while the cathode tube was covered up.

He tried to block the rays to disturb the glow, without success, before placing his hand in front of the tube. Röntgen was stunned to see his bones in the image projected onto the screen.

He continued to experiment and learned the images could be photographed, producing a simple version of the x-ray we know today.

However, the damaging effects of the x-rays weren’t known for some time. Initially, scientists believed there were no risks associated with the technology at all, but as their use expanded, there were reports of injuries, skin damage and cases of cancer due to high, repeated exposure to the radiation. This is why doctors, dentists and nurses will now step away while x-rays are taken - but it remains perfectly safe for patients during check ups.

Röntgen never patented his discovery, gifting his accidental invention to the world. He was awarded the first Nobel Prize for Physics in 1901.

Cosmic microwave background radiation

They initially thought it was pigeons. It was actually proof of the origins of the universe.

In May 1964, two American researchers at Bell Telephone Laboratories in New Jersey, Robert Wilson and Arno Penzias, were conducting experiments when they heard a strange noise.

They were working with a device known as the Holmdel Horn Antenna, that could detect radio waves bouncing off balloon and communications satellites.

The antenna was incredibly sensitive and the radio waves were weak, so they needed to eliminate all possible interference so they could determine what the noise was.

That led them to the pigeons. Some of the birds were nesting near the antenna and had even left a dropping or two. Wilson and Penzias cleared the area but could still hear the buzzing.

It was then that they realised it must have been coming from outside of our galaxy.

By coincidence, at the same time researchers at neighbouring Princetown University were looking for radiation they believed was left over from the Big Bang.

They realised Wilson and Penzias’ discovery was cosmic microwave background radiation – the ancient and first light that filled our universe 14 billion years ago, and proof of its origin.

The discovery earned the US duo the Nobel Prize for Physics.

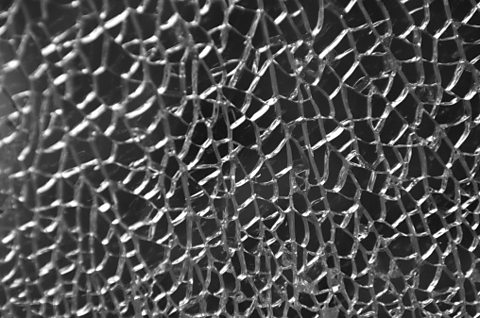

Safety glass

The glass in car windows, public building windows or in cookware and kitchens isn’t the same as regular glass.

It’s safety glass – strengthened to be less likely to break and fire resistant. If it does break, it’s designed to shatter into small pieces that are relatively harmless.

But safety glass was only cracked – so to speak – by accident.

In 1903, French chemist and artist Édouard Bénédictus was working in his lab when he knocked over a glass, that contained cellulose nitrate – a liquid plastic.

Instead of breaking into many pieces, the glass simply shattered, and kept much of its original shape.

Six years later, after hearing about people injured in a car accident by shards of glass, Bénédictus patented his idea. He went on to form a company that made car windscreens out of a glass and plastic hybrid.

Matches

Before 1827, lighting a fire was particularly hard work.

So, we have John Walker from Stockton-on-Tees to thank for making the birthday cake candle lighting process significantly easier.

In 1826, the pharmacist was experimenting with a chemical paste for use in guns. After mixing the solution with a wooden stick, he accidentally scraped the stick across the hearth by his fireplace and it caught alight.

Walker refined his ‘friction matches’ over the next year before selling them. The first matches were made of cardboard before he then used small, wooden splints. Finally, he added a sandpaper stripe to the side of the matchbox, to be struck to light the match.

Despite being encouraged to do so, Walker didn’t patent his idea, which was then copied by Samuel Jones of London two years later and mass produced.

Artificial sweeteners

If you enjoy drinking the occasional sugar-free soft drink or chewing a piece of gum, you might have a case of accidental poor hygiene to thank for its existence.

Saccharin is one of a number of sugar alternatives known as artificial sweeteners found in different foods and drinks.

It was discovered by chemist Constantin Fahlberg in 1879. Working at John Hopkins University in Maryland, USA, Fahlberg was researching coal tar – the thick dark liquid created in the production of coke (the fuel, not the drink) and coal gas from coal.

While working in his lab, he paused to eat a meal his wife had prepared and noticed it tasted unusually sweet. He then realised he’d forgotten to wash his hands before eating and they were still covered in coal tar by-products.

Fahlberg later named his discovery saccharin – its use became widespread following the rationing of sugar during the first World War.

Five things science still can't explain

Yawning, cats purring, and the curious case of the tomato

Marie Van Brittan Brown: The woman who made our homes feel safer

A bespoke poem for Bitesize, by Sophia Thakur, as part of Black History Month.

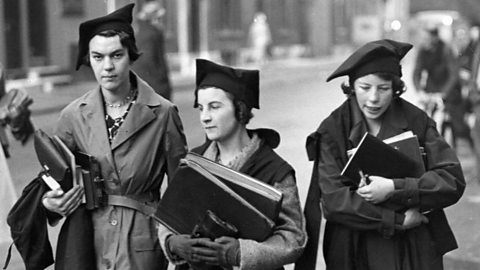

'They couldn’t go on the river with a man on their own'

The changing lives of Oxford’s female students