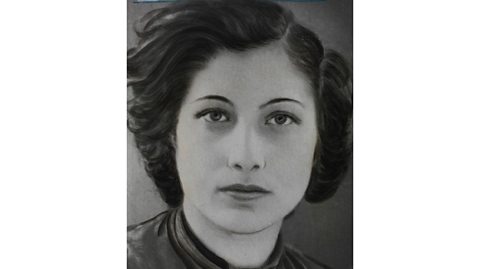

The Nazis never learnt this female spy's real name during World War ll. Have you heard of her?

The story of Noor Inayat Khan's bravery features in a new exhibition called Spies, Lies and Deception, at IWM (Imperial War Museum) North.

BBC Bitesize spoke to expert Shrabani Basu, author of a book about Noor’s life, plus the curator of the exhibition, Amanda Mason, to find out more.

An unlikely spy

Noor was not your typical secret agent. Descended from Indian royalty her dad was a Sufi, the branch of Islam that celebrates music and meditation. Her mum was American and Noor herself was well travelled and educated; she studied psychology, was a musician and children’s author.

Noor and her family left Paris to join the war effort; “She made a promise to the people of France, that she would come back,” says Shrabani. “When war broke out though she was a pacifist and believed in non violence, she felt she couldn’t stand by and watch.”

Aged just 26, in November 1940, Noor joined the WAAF, the Women's Auxiliary Air Force. She was in the first batch of women to be trained as a radio operator.

In 1942 she was approached by the secret service Special Operations Executive (SOE) was a British organisation formed in 1940 to conduct espionage, sabotage and reconnaissance in German-occupied Europe and asked if she wanted to become a spy. She was told she’d be sent in to France with no protection and she’d be shot if she was caught. Noor took the job.

How to train as a World War ll spy

Noor had been learning morse code but everything changed at spy school and she was put through intense physical training. Noor was taught to how to handle weapons, how to kill in the dark, how to run and climb.

But some of those who trained her were unsure about her suitability, says Shrabani; “She had to learn how to handle a gun. She hated it and in their report, her trainers said she was scared of guns. But she also knew she had to do it, so she did.”

Noor was taught other spy skills too: how to recruit sources, what was a a location where you leave a message and somebody knows where to pick it up from and a where a person takes or delivers a message in code. She learnt all about the The Nazi’s secret police force, French collaborators and was schooled on the streets of Paris, where she was to be sent.

A code name and cover story was given to Noor - she had to pretend to be a children’s nurse called Madelaine. In case she was caught, the instructors ran mock interrogations, dragging her from her bed in the middle of the night. Shrabani tells us that their reports showed that Noor was terrified; “Even though she knew she was safe at the school, she was trembling, a wreck. And they said, how will she stand up?”

Examiners at the SOE still had some doubts but wrote that Noor also had a steely side, says Shrabani; “Under interrogation, they were confident she wouldn’t give away anything because she said, I just won't speak.”

Noor’s World War ll mission

June 1943 and Noor was sent over to occupied France. Her mission, as part of a team, was to supply arms and ammunition to help the French Resistance. Noor was to be one of the radio operators sending messages back from France.

Arriving in occupied Paris, there were swastikas hanging from every big building. “It was terrifying for someone who grew up there and then had gone back,” says Shrabani.

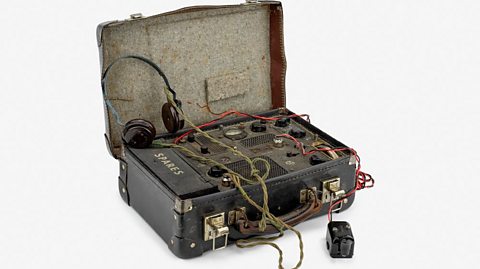

Noor’s mission set her on a cat and mouse game with the Gestapo; “She was on the run carrying this wireless, disguised in a suitcase, and she had to take it everywhere.”

Noor often felt like she was being followed but she had a network of contacts that she could use. Shrabani explains Noor's friends, her music teacher, doctor and dentist, “everybody loved her from when she lived there and of course they just let her in and she transmitted from all these places.”

Noor survived, working like this for three months; “London was absolutely amazed by what she was doing,” says Shrabani. “A wrong message could have meant life or death but she was accurately sending her messages in difficult circumstances, and they received them loud and clear.”

Image source, IWM

Image source, IWMOccupied Paris: a spy’s pov

But as the months progressed the rest of her team was captured; “She was all alone in Paris, doing the work of six radio operators and the courier,” says Shrabani. “She was meeting agents in the field, handing over money and telling them where they have to collect arms, and of course, reporting everything back to London.”

At that point in the war, the average life expectancy of a radio operator in occupied France was six weeks; ”Initially it was men who were sent in and they were just dropping dead like flies, not surviving, so that is why they started training women,” says Shrabani.

Because Noor was the first woman radio operator to be sent undercover to France, the Germans had no idea they should be hunting for a female spy. Shrabani points out that when they captured her other colleagues, “they knew a radio operator was still missing but they were looking for a man.” But under interrogation, one of her fellow agents mentioned her code name and the Germans then realised they should be looking for a woman.

London told Noor to come home at this point, says Shrabani, “they said you've done your bit, you've been there a long time and it's very dangerous.” Shrabani believes Noor would have come back, but she is betrayed by the sister of a fellow agent before she can.

Captured but never defeated

Noor was arrested but she didn’t go quietly. Taken to Gestapo headquarters in Paris, Noor made two escape attempts, the second might have succeeded if not for a RAF bombing raid; “They had loosened the skylights and got out on to the roof,” but unfortunately the air raid sirens went off; ”The Gestapo checked the rooms and found three prisoners missing, so they got them,” Shrabani says.

Noor was then sent to Germany, to Pforzheim, a women's prison in the Black Forest. She was held there for 10 months; “Noor’s story is so dark,” says Shrabani, “but what is inspiring about it is how in every situation, she never gave up.” In prison Noor was kept in chains, in isolation but she refused to reveal any information. Her captors didn't even find out her real name.

But in September 1944, she and three other female SOE agents were transferred to Dachau concentration camp where on 13 September they were shot; “Noor goes down screaming ‘Liberte’,” explains Shrabani, “so they get her body, but they can't break her spirit.”

For her courage, Noor Inayat Khan was posthumously awarded the A medal created by King George VI on 24 September 1940 that recognises acts of extreme bravery carried out by civilians and military personal when not under enemy fire in 1949.

Remembering the human side of espionage

Noor is an important inclusion in the exhibition at IWM North says Shrabani, because her story is such a different one; “Her immense bravery, her loyalty. Her male colleagues broke under interrogation, but not Noor. She did not reveal anything. And right till the end, they did not even know her name.”

“Also her background” Shrabani adds that Noor was an educated woman from a South Asian background “the fact that she was somebody who believed in non violence. She was doing this out of a deep belief that we had to fight for democracy.”

Spies, Lies and Deception: the exhibition

This exhibition brings together stories of espionage and deception from the First World War up to the present day. These help explore the different perspectives behind spying and espionage, when you are the spy or the spied upon.

Amanda Mason is the curator who has brought it all together: “We start by looking at the process of creating deception and showcase some of the most famous cases. Then the exhibition flips it and examines the opposite; “What's it like when somebody is spying on you? What are the tools that have been used over the years to uncover plots and to find spies lurking in our midst?” says Amanda.

And then the final stage of the exhibition asks what was the human cost for the people who were at the sharp end? Amanda explains, “with Noor and SOE agents like her, they were subject to this deception that involved their radios being taken when they were captured.” The Germans worked out how they could use their own radios against them and played false messages back to London.

”So somebody like Noor, she's a victim in that process. So that's why in this section we want to look at the aftermath or the cost of deception,” says Amanda.

Spies, Lies and Deception at IWM North in Manchester, runs from November 29 2025 to August 31 2026.

Showcasing over 60 objects including gadgets, classified documents, art, film and photography, this free exhibition uncovers the secrets of extraordinary individuals who risked everything.

This article was published in November 2025

Much better than a Bond movie: What it's like to be a real-life spy

Meet Hannah, whose job is so secretive that we can't even use her full name.

The ultimate fictional spy quiz

Your mission, should you choose to accept it, is to test your secret agent knowledge.