A long time ago, before the internet existed...

Before the internet existed and before computers were in lots of homes and offices around the country, letters, information records and essays had to be written up on a typewriter. If you made a mistake there was no delete button, no chance to edit it, you simply had to type the page all over again.

But thanks to a single mum working as a secretary in 1950s Dallas, Texas, things were about to get a whole lot easier. Cooking up the idea in her kitchen, Bette Graham invented the first ever correction fluid - that white liquid you can paint over your mistakes with (Tipp-Ex didn’t come along until 1965). It became an office and pencil case staple around the world, making her a millionaire.

"I was just trying to be a better secretary"

Shortly after the Second World War, Bette Graham’s first husband left her and her teenage son, so she had to find work to support them both. Having worked as a secretary before she married, Bette started at Texas Bank, but found their brand new electronic typewriters tricky. “My fingers would hang heavy on the sensitive keyboard”, she said, “the first thing I'd know I'd have a mistake which I simply couldn't erase.” Bette’s typos piled up and, as a busy secretary, she didn’t have time to relearn how to type using this new technology.

BBC World Service show Witness History took Bitesize down to the archives to find out more.

Setting the world (and kitchen) on fire

Bette had grown up with her artist mum, she loved drawing and painting herself, and knew that artists just painted over their mistakes. That gave her an idea. Bette said: “I went home and got a bottle, put some white pigment in some solution and took my little watercolour brush to the office.” She then began to correct her mistakes using the solution. Bette admits that it was a simple plan in the beginning. She didn’t intend to invent a product for worldwide distribution. “Nor was I trying to think of a way to make a million dollars. I was just trying to be a better secretary”, she added.

Her idea worked - Bette’s boss didn’t notice the cover-ups and when she showed this magic liquid to her secretary friends, they wanted some too. But Bette wanted to improve it first; how the liquid absorbed into the paper and make it dry quicker. She went to the library to find different formulas and contacted chemical companies to request samples of products. Then, Bette said it was time to experiment: “I put that formula together in my kitchen just from my own knowledge… But of course I'm not a chemist and I made lots of mistakes, in fact I caught my kitchen on fire at one time.”

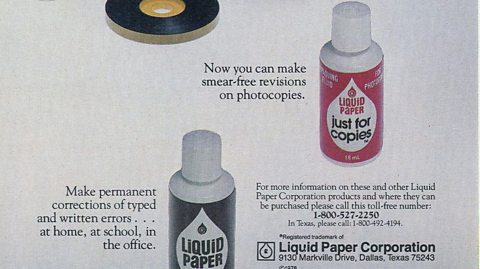

Using small nail varnish bottles with brushes for her concoction, Bette and ‘Liquid Paper’ were in business. She sent samples to office supply magazines (that’s how we used to order things before the internet) and was soon overwhelmed by all the inquiries. She said: “I would work all day as a secretary and sometimes work all night answering the mail."

From single mum who nearly blew up her kitchen to global businesswoman

By 1962, Bette was selling around 1,000 bottles a week. She gave up her job and enlisted help from close to home. She said: ”My labour was my 15-year-old son and his friends who would work after school, I paid them a dollar an hour.”

Life for Bette was on the up as production moved from her kitchen to a trailer in the garden and she married her second husband Robert Graham. He helped her run the business, driving from city to city selling the fluid to office supply companies found in the phone book.

Bette said: “Most of the secretaries in these little offices make the decisions about office supplies,” and secretaries loved Liquid Paper because it saved them time and costly mistakes. By 1965 the company had nine employees and an automated production line, they went international with plants in Canada, Belgium and more followed. By 1973, that single mum who nearly blew up her kitchen, had created a global business, selling 25 million bottles a year.

A millionaire who wanted to give back

Despite building a successful business, Bette’s marriage ended in an acrimonious divorce and Robert tried to push her out of the company in 1975. He also tried to change the formula for Liquid Paper, which would remove Bette’s right to royalties from future sales, but she managed to maintain control. In 1979 Bette arranged the sale of her company to Gillette for a staggering $47.5 million.

Bette was keen to inspire others, particularly women. She had designed her company offices to include on-site childcare, a library and green space. She also set up charitable foundations supporting women’s welfare and development in business and the arts. She said: “I know from experience that if you think your job offers you no opportunity for innovation or creativity that you are wrong… it is possible for you to have growth right where you are.”

Her entrepreneurial spirit inspired the next generation

One man who was always in Bette’s corner though was her son, Michael, who was Bette’s first employee, packing boxes in their kitchen. He used the inspiration his mum provided to be creative in his own way as a member of the 1960s band The Monkees.

Laurie E. Jasinski from the Texas State Historical Association explained to us that people think of the 1950s as a time for traditional homemaker roles for women, but she said: “We have seen that many women also were conscientious contributors in the workplace.” Laurie points out that at the time, these women worked hard in their respective careers as well as at home for their families. And their entrepreneurial spirit inspired the next generation. She added: “Bette obviously influenced her son Michael, who went on to excel in the music business as one of 1960s band The Monkees and was a key player in early music video production.”

Michael was his mum’s biggest fan. She even appeared on the show and he used his fame to help promote her business. Michael was recorded as saying: “While I was making music with The Monkees, a very smart secretary was also coming up with another number one hit. Liquid paper correction fluid. That secretary was my mom. Great idea, Mom.”

Bette Graham died in 1980 at the age of 56, leaving half her estate to her son and the rest to charities. Bette said she wanted to leave a legacy explaining that: “My estate will be what I can do for others. I want to see my money working, causing progress for people.”

And despite the rise of computers and autocorrect, correction fluids are still sold in office supply shops today.

Bette Graham's story is part of the BBC World Service’s 'Witness History' series, you can listen to this episode, and others in full here.

This article was published in September 2025

Quiz: What is your perfect job? quiz

Try this fun quiz to find out about the types of jobs you might enjoy and different careers you could consider.

Quiz: How could AI affect your job? quiz

Find out how savvy you are about the future of AI at work.