It all began with a hypnotic sequence of spirals.

Elements of the opening titles to Alfred Hitchcock’s 1958 thriller Vertigo - which look like Spirograph drawings brought to life - have been cited as the earliest example of computer generated imagery (CGI) in film. Computer animation pioneer John Whitney fed complex mathematical equations into anti-aircraft technology left over from World War Two to create them. Less than four decades later, Whitney’s successors would create the dinosaurs of Jurassic Park - making CGI a household phrase.

But what happened before filmmakers could ask a team of computing wizards to rustle up an alien world or fantasy creature? They had to rely on a different type of creativity and ingenuity - and still got results, as BBC Bitesize found out.

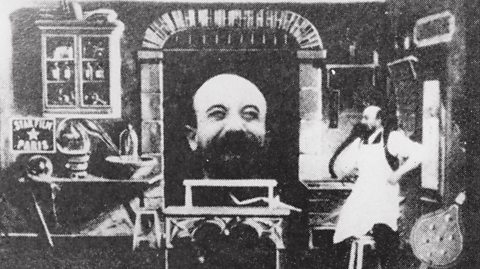

The Man With the Rubber Head: Inflation in France

As the 20th Century began, professional magician Georges Méliès embraced early cinema with gusto. Thanks to him, we have movie trickery and techniques still in use today. Slow motion and fading to black (or the fade out) are just two of his innovations.

His 1902 science-fiction short, A Trip to the Moon, is perhaps his best remembered. The famous shot of a rocket embedded in the Man in the Moon’s face is just one of many special effects peppered throughout the film - and was even glimpsed during the opening ceremony of the Paris 2024 Olympic Games.

A year earlier, Méliès demonstrated a different kind of trickery in The Man With the Rubber Head, also known as A Swelled Head. In the short silent film, he played a chemist who could inflate a talking head (also played by Méliès) with a pair of bellows, then deflate it.

It looks a relatively simple effect, but reports of the filming reveal the complex maths Méliès worked out in advance. He was in a cart on rails, moving towards and away from the camera. This made his head appear to inflate and shrink, while his sums kept it in proportion with the rest of the scene.

Modern Times: Skating close to the edge

Silent films were all that cinema could offer at first, but they weren’t as common by the 1930s. Talking pictures had debuted in the late 1920s and the pressure was on early film stars, such as Charlie Chaplin, to bring speech into their world.

In 1936, Chaplin made Modern Times, essentially a silent movie but with occasional dialogue and music. It was the final appearance of popular character The Tramp, and showed him trying to keep up with the new technology and increased industrialisation of the 20th Century. Sound wasn't the only innovation in Modern Times - some impressive special effects were on show too.

Image source, Modern Times - Charles Chaplin Productions/ United Artists/ Roy Export S.A.S. Director: Charlie Chaplin

Image source, Modern Times - Charles Chaplin Productions/ United Artists/ Roy Export S.A.S. Director: Charlie Chaplin In one scene, The Tramp tries to impress his friend, Ellen (Paulette Goddard), by roller-skating while blindfolded in the toy section of a department store. It takes him perilously close to a sheer drop where repair works are taking place and the guard rail is missing.

Chaplin, an accomplished roller-skater, was never in any danger. In reality, there was no drop.

The floors below were a matte painting. This was a highly detailed image, most likely painted on glass, and precisely placed in front of the camera to give the seamless illusion that it is part of the scene. The only element on the studio floor was the curb at the edge of the drop.

The Ten Commandments: Amazing walls of water

Cecil B. DeMille was a director who made films on an epic scale. When he made the biblically-themed The Ten Commandments in 1956, it wasn’t even his first attempt at telling the story. In 1923, he had turned a section of the sand dunes near Guadalupe, California, into a vast set representing Ancient Egypt for a silent, black and white version of how Moses led the Israelites to safety from slavery.

More than 30 years later, DeMille could remake the film in sound and colour. But, he also faced the same challenge as first time around - convincing the audience that Moses (played by Charlton Heston in this version) could part the Red Sea and enable the Israelites to escape the approaching Egyptian army.

In 1923, DeMille had used jelly to create a pair of (slightly quivering) walls of water that were blended in with footage of people crossing a desert floor. This time around, the effect was so impressive it became - arguably - the movie’s defining moment.

To achieve it, gallons and gallons of water were dropped from above into a U-shaped trough at the film studios in Los Angeles. When the shot was reversed, and combined with footage of Moses and the Israelites making their escape, it gave the illusion of a safe path opening up on the sea bed as two huge waves rolled away from each other. Once Moses and his followers were across, the footage was ‘un-reversed’, bringing the waves together once more.

Jason and the Argonauts: Skeletons, swords and sorcery

Movie magic can require patience. Hours of it. One man who could vouch for that was Ray Harryhausen.

From the 1940s to the 1980s, Harryhausen specialised in creating highly detailed, articulated models brought to life using stop-motion animation.

These model sequences were married together with live action footage to create exciting scenes in various fantasy-themed films including, famously, the 1963 film Jason and the Argonauts, where the hero of the title is tasked with finding the Golden Fleece. As Jason nears the end of his quest, an army of seven skeletons burst up from the ground to stop him taking the Fleece. The battle scene, where skeletons wielded swords, spears and shields, runs for just under five minutes and took Harryhausen three months to animate. It became a huge favourite with audiences and, such was the quality of his craftsmanship, the skeleton models still feature in exhibitions of his work.

Tron: The future glows blue

Around 15 minutes’ worth of this 1982 Disney film is pure CGI.

While that should disqualify Tron from this list, the film’s futuristic look is not all down to computer wizardry. The finished product is also a mix of live action and traditional animation.

The cast of Tron filmed in completely black studios, wearing white costumes with black detailing. The filming process was so devoid of colour that star Jeff Bridges commented on how overwhelming it could be to step back into the ‘real world’ after a long time in the studio.

When Tron was released, the suits worn in its cyberspace world had a futuristic blue glow. This wasn’t CGI, but a traditional animation technique called backlighting. The black detail on the white suits was removed from the An image usually found on a strip of transparent film. The lightest colours are the darkest, and the darkest are the lightest, in contrast to how they appear in reality., leaving transparent gaps. When a blue light was shone through the film, it could be seen through the spaces, giving it a satisfying glow.

Tron marks one of the earliest examples of traditional filmmaking working alongside the sleek imagery that computers can create. As time went on, that innovation would become a tradition in itself; enabling toys to tell stories, young wizards to fly on broomsticks, and Avengers to assemble.

This article was published in July 2024

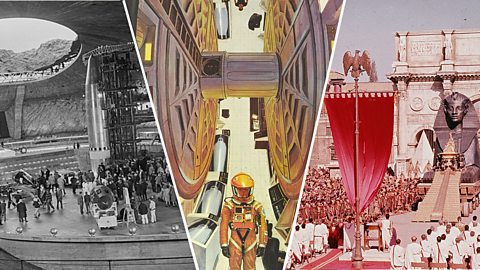

Five of the most amazing film sets in history

How the worlds of James Bond, Lord of the Rings and Cleopatra were created in jaw-dropping scale

The UK film locations crews keep coming back to

Why you've seen the same castle in Harry Potter and Transformers

Five times the movies got their science right

Science fiction often has scientists’ eyes rolling, but some film writers and directors have gone above and beyond to get their facts spot on.