‘If my vitiligo vanished, I’d be distraught’

- Published

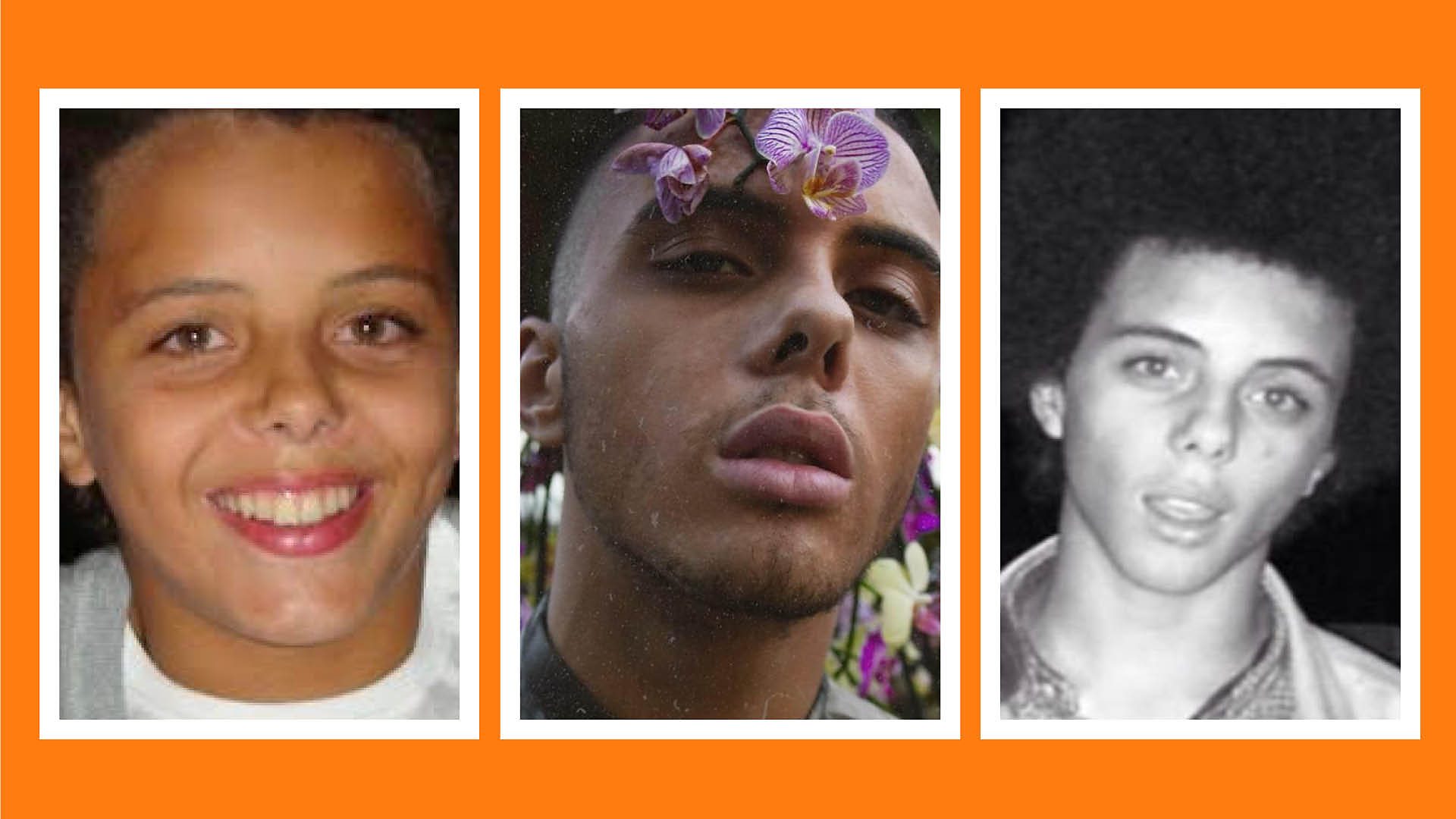

Alec spent a decade wishing for a cure, but now he’s showing the world his skin

I was six when I first noticed there was something wrong with my skin. I was on holiday with my mum in Tenerife, when one night I felt hot, sweaty, and couldn’t sleep. The next day I spotted these tiny patches of white on my fingers.

My mum had no idea what it was. She’s a nurse and has worked in the NHS for almost 40 years, but she had never seen this before. She asked me if I’d put my hands in bleach.

It was over a year before I heard the word ‘vitiligo’. By then, more white patches had started appearing on my body and face. I saw lots of doctors but it took time for them to work out what kind of skin condition it was.

I really wanted to hear someone say that it would go. I saw skin specialists who advised me to try steroid creams and UV light therapy, but none of it worked for me. Eventually, when I was almost eight years old, my specialist diagnosed it as vitiligo - a condition which has no cure. It can get better, then it gets worse again.

My mum was the one who broke the news to me. The doctors would talk to her and she’d break it down for me. It was really hard for her to watch her son struggling with body confidence issues at such a young age, but she handled it in the best way possible.

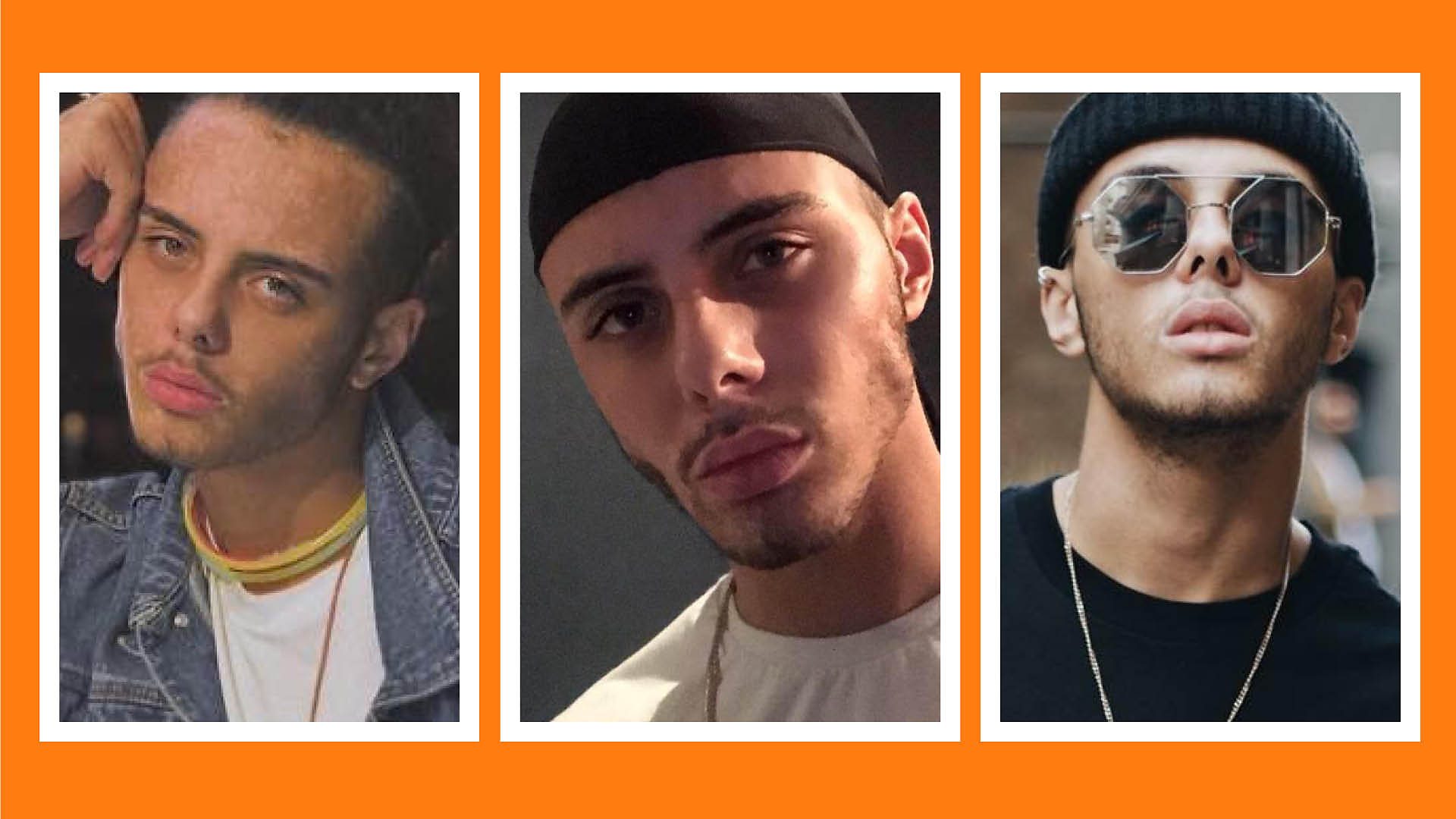

It has taken a decade for me to accept my vitiligo as part of me. My hands were the first thing I stopped trying to cover up. My face took longer - it was much harder for me to let people see how I really look. I’m 20 now and not once in the past two years have I wished for a cure. My skin’s been pretty stable in that time too.

People with vitiligo often hide it with make-up. It’s a condition that affects 1% of the world’s population, external, but it’s not really talked about. Areas of skin – especially around the eyes, nose and mouth - lose their natural colour and turn white. It affects men and women of all ethnicities equally, but obviously it’s easier to see on people with darker skin. Nobody knows what causes it. Some people think that stress is a trigger but when I got vitiligo, I was just a kid on holiday living my best life.

When it appeared, one of the hardest things for me was feeling like I was losing part of my identity. My mother is white and my father is from Barbados. Getting vitiligo felt like part of my ethnicity was being taken away.

The bullying at school was bad at times. People would make racist comments and say things like, “the black is washing off”. Sometimes I would get angry and retaliate, but I often let things slide - I didn’t want to isolate myself any further. I already felt so lonely.

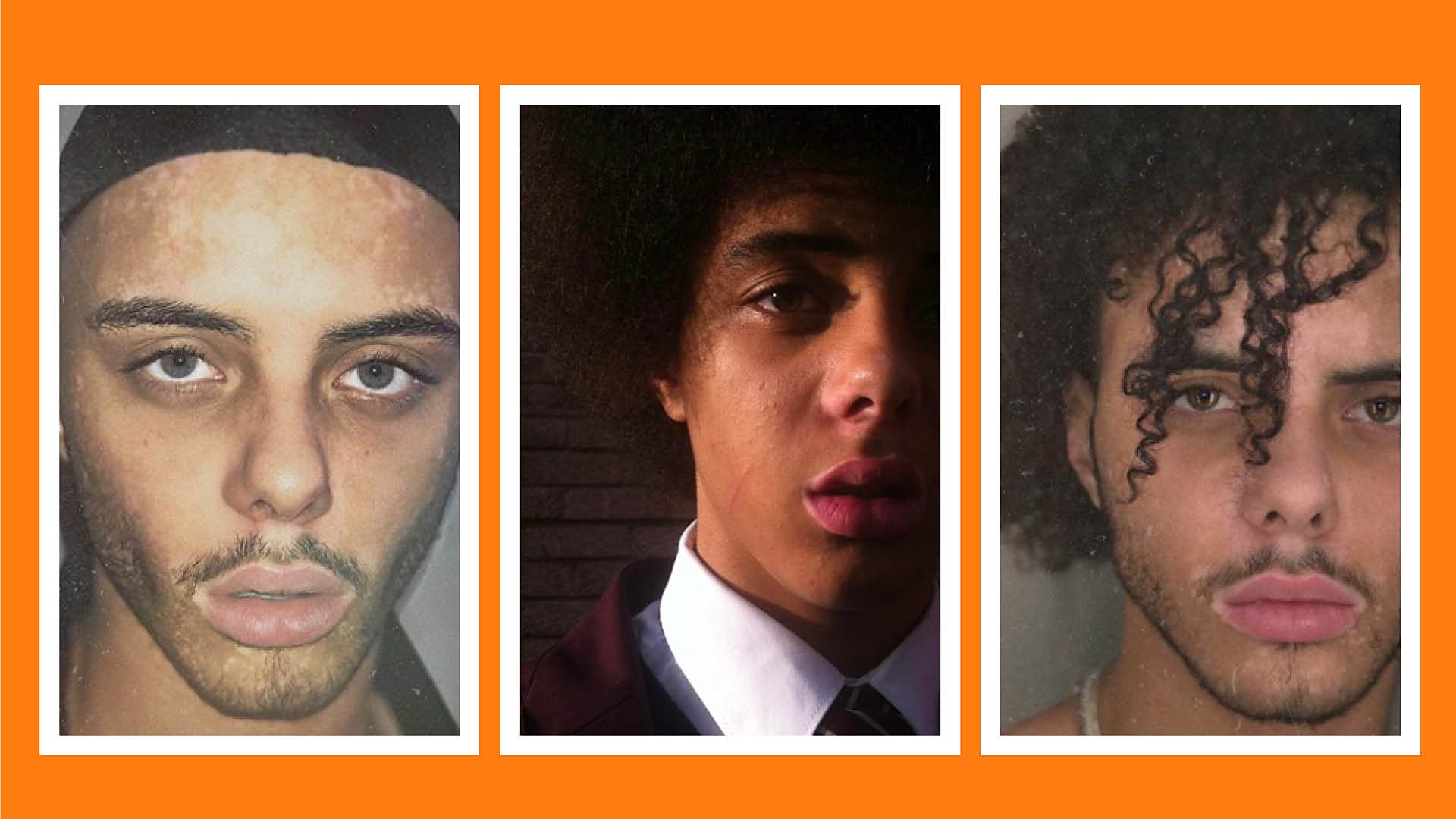

When I was 12, I decided to cover it up with make-up. My doctors sent me on a camouflage make-up course, where I learnt how to blend six different powders and pastes to match my skin tone. It took me nearly an hour to apply it all at first, but I got that down to 15 minutes.

For me, that make-up was my comfort blanket. It gave me the confidence to make friends and go to parties. But I was still paranoid. I was always worried that my face had smudged or that it was wearing off. I would check it constantly throughout the day.

And it didn’t help with the bullying. People at school would tease me about it. The worst part was that my lips are naturally very pink, so when the skin around my mouth turned white it highlighted them, and it looked like I was wearing lipstick.

Now I’m so close to my friends that I tell them everything, but back then I didn’t want them to know how my skin really looked. I avoided staying over at their houses. If I crashed after a party, I would insist on sleeping on the sofa and would search out a non-white pillowcase so I didn’t leave make-up stains everywhere.

Once, I was at a friend’s house and we fell asleep on a bed with fancy white pillow cases. In the morning, my side profile was staring up at me.

My rock bottom came when I was 15. It started hailing one morning when I was walking to school. My afro-hair was down and it trailed across my face leaving streaks. Cream and powder were running down my face - I looked like a melting waxwork. I snuck into the bathroom to fix my face. I thought I had sorted it but then I noticed a stain on my white t-shirt. I just collapsed on the floor, weeping.

All I could think was, ‘Why is this my life?’

In that moment, I realised something had to change. So a few weeks later, during the summer holidays when I wouldn't be around everyone from school, I decided to stop wearing make-up. I’d already started showing my vitiligo to my closest friends; my mum would invite them round for dinner and I didn’t feel like I had to cover up in my own home.

Finally, I turned up to meet them all to go to a party with my patches clearly visible. My friends just treated it like it was nothing. I was so relieved, but part of me wanted to shout at them, “Is that your reaction? Do you have any idea what I’ve been through?” My best mate was so chilled about it, I almost felt like hitting him. And I felt kind of foolish for beating myself up so much about it.

Things changed from them on. When it came to chatting up girls, I was quite confident. Nobody ever mentioned my vitiligo and by the time I was old enough for a proper relationship I was comfortable with it. The worst remarks usually came from parents’ friends – we’d be sat round the dinner table and they’d say things like “what’s that on your skin, Alec?”

Some people still tried to cut me down at school, but my friends always had my back. It helped when I got spotted by a talent scout a few months later, and signed to a modelling agency. That gave my confidence a real boost. It helped me see my vitiligo as an asset, something that makes me stand out - in a good way. My face was on a billboard in east London recently, with my vitiligo clearly visible. It was a surreal and proud moment.

Now, thanks to my modelling, I can talk about my experience in public and help others. I even get parents of kids with vitiligo messaging me on social media asking for advice. I still have good days and bad days but now, if I woke up one day and my vitiligo had vanished, I’d be distraught. It’s part of who I am and always will be.

As told to Serena Kutchinsky

This article was originally published on 2 May 2018.

Alec's story is onMisFITs Like Us on BBC Three iPlayer