Using my first tampon put me in A&E

- Published

That's how I discovered I had a problem with my hymen

Warning: this article contains adult themes, and some external pages we've linked to contain anatomical images

Like most teens, I was a little nervous about using a tampon for the first time. I'd just got my period, right before a summer holiday where I'd been really looking forward to taking dips in the pool.

I knew a bit of discomfort and perhaps some pain was possible the first time I put one in, and it did take a few attempts, but to my relief, inserting it didn't cause me too much trouble. According to the googling I’d been doing, getting it in was the hard part, external - so my 16-year-old self assumed that getting it out would be a breeze.

How wrong I was. Fast forward a couple of hours, and I was experiencing my first-ever panic attack after spending two hours desperately yanking at the string in an increasingly frenzied bid to remove it. I was clueless as to what had gone wrong and, even more scarily, so was the internet. “Pull it harder, don’t be shy,” someone had written on an online health forum. “Get in the bath: the tampon isn’t saturated enough, so the friction is too great,” suggested someone else. But, the more I pulled, the more pain I was in. The bathtub solution? No luck.

It was only when I plucked up the courage to have a look in the mirror that I realised why the tampon wasn’t budging. My heart sank as I saw a thick, fibrous string of tissue stretching across the bottom of the now expanded tampon.

Why was my own body conspiring against me? That was all I could think as my equally baffled mum drove me to hospital in a panic that night. A few hours later in A&E, a female doctor eventually managed to wrench it free, as I yelped with pain. She told me that the string-like piece of flesh was simply a part of my hymen that was yet to wear down and would gradually come away after I started having sex. But the thought of experiencing that kind of pain again - especially in a situation that was supposed to be pleasurable - was horrifying.

Unsatisfied with the doctor’s verdict, I turned again to the internet and discovered that I might have something called a septate hymen, external. I still went on holiday but I avoided the pool - I didn’t want to go near another tampon. At least I’d tried to use one before I went, because if that had happened while I was away it would have been even more of a nightmare.

Georgia Watts now wants to raise awareness of hymen abnormalities

Two weeks later, I went to see my GP and told them what I’d found out online. When she examined me, it was so painful that she was unable to confirm whether my suspicions were correct or not. But, after I explained what had happened with the tampon, she decided to refer me to a gynaecologist.

By the time I went to the appointment around a month later, I was terrified that there might be something more serious wrong with me but, after a brief examination, the gynaecologist immediately confirmed what I’d suspected. In that sense it was actually a massive relief.

I was booked in for a simple surgery, external called a hymenectomy to remove the extra tissue and stop the vaginal opening from being obstructed, external. While I knew that penetration wouldn’t be a physical issue anymore once I'd had the op, I was still worried about how that experience, and the surgery, might affect me psychologically in the long term. Because I’d had my first (and only) panic attack as a result of the condition, I was afraid that I might always associate penetration with the trauma of that night.

At this point, I opened up to my group of friends at school about what was happening, and they were really supportive - especially when I had to take a couple of days off school for the operation. Thankfully, the surgery was a complete success, and the physical recovery was pretty straightforward. But, it’s taken longer to recover emotionally. Even now, nearly four years later, I still haven’t plucked up the courage to use a tampon again, even though I know it would be fine.

These days, I'm keen to share my story to help people understand more about hymen abnormalities and how they can affect people at a really formative time in our lives.

The hymen, external, a ring of skin that usually partially covers the opening of the vagina, typically forms in the shape of a half-moon but, as I found out the hard way, that isn’t always the case. My hymenal membrane had a band of extra skin stretching across the middle, creating two small openings rather than one. This is a congenital irregularity, meaning that I was born with it.

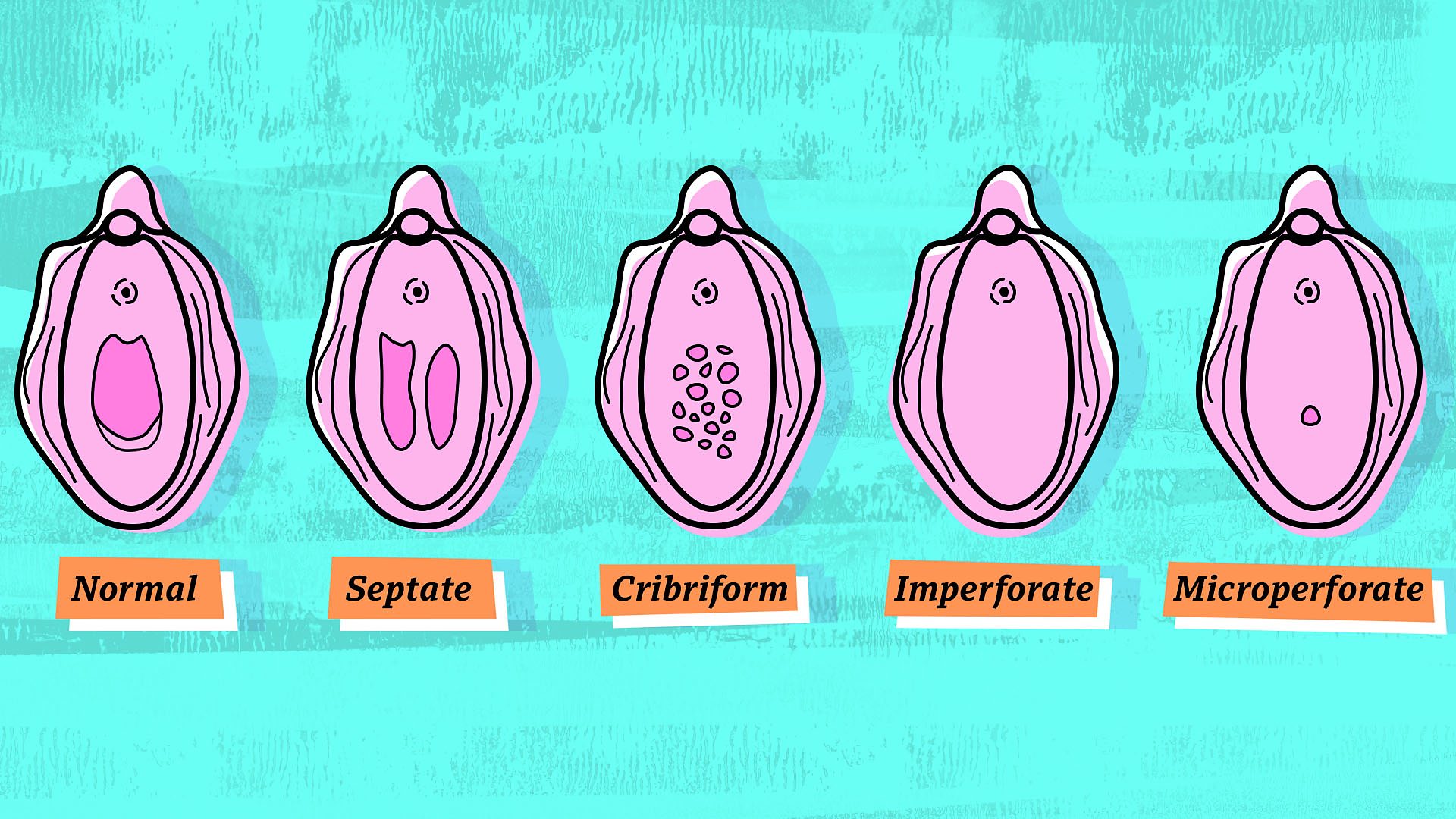

A septate hymen, like mine, isn’t the only kind of hymen abnormality, external some women experience. Hymens can also be imperforate, external, microperforate , externalor cribriform, external. An imperforate hymen is where the vagina is totally, rather than partially, covered by an intact hymen, says consultant gynaecologist Dr Caroline Overton. Microperforate hymens have just a tiny opening and cribriform hymens have multiple small openings.

Different types of hymen abnormalities

Having an imperforate hymen “makes tampon insertion and sexual intercourse impossible”, says Dr Overton, as the opening to the vagina is completely blocked. Meanwhile, with the other three kinds of hymen abnormality, including the kind I had, sex can be possible but it is likely to be “very painful”. These kinds of problem “may only be picked up when women choose to start using tampons,” Dr Overton adds.

Since painful sex can be a symptom of a number of other conditions, from thrush, external to lack of arousal, external, people may not even realise they have a hymen abnormality.

If you’ve never heard of these conditions before - you're not alone. While all four are relatively rare, the imperforate hymen, which Dr Overton believes is the most common of the four, affects between one woman in every thousand and one in every ten thousand, external. That means between 3,200 and 32,000 women in the UK may be affected. There is little information available online about hymen abnormalities, and they certainly weren’t covered by my school sex education.

Since having surgery, I haven’t experienced any further issues, but I’ve spoken to other women online who haven’t been so lucky. Gemma,* who’s in her mid-30s, discovered that she had a microperforate hymen, where there’s only a tiny opening, during an internal examination at a health clinic back in 2003, when the doctor was unable to insert even a cotton bud.

“It was mortifying,” Gemma says. “I was raised to ‘save’ myself for marriage, only to find that waiting had delayed an unpleasant discovery – I needed corrective surgery. I didn’t tell anyone except one girlfriend for fear of being ridiculed. I didn’t want anyone talking about something so deeply personal and intimate.”

Unfortunately for Gemma, a hymenectomy wasn't the end of her problems, as it had been for me. Instead, she developed vaginismus, external, a condition where the vagina spasms and tightens when penetration is attempted, making tampon use and penetrative sex difficult or impossible.

Gemma says that she believes an “exceedingly rough” examination post-surgery that left her “crying and bleeding” caused her to develop the condition.

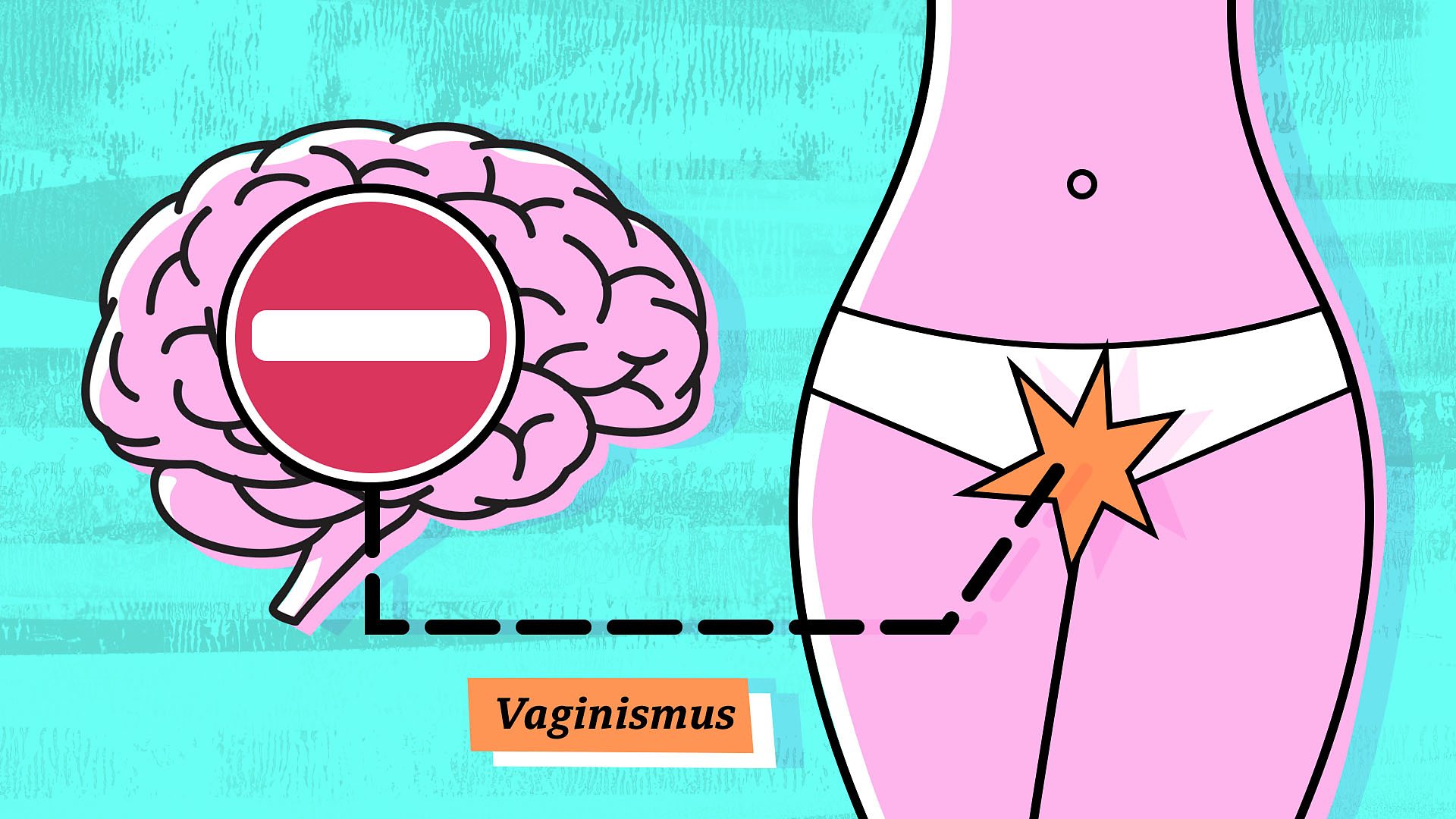

Vaginismus is thought to occur when the body experiences physical trauma, change or pain

“The brain is subconsciously protecting the body from invasion,” according to psychosexual and relationship therapist Sarah Berry from The Vaginismus Network. “It can happen when the body experiences physical trauma, change or pain. It can also occur if someone’s perception of their body, sexuality, or anything else that could affect the vagina changes. So, if someone discovers that they have an abnormal or perforated hymen, this could be very triggering.”

Despite undergoing physical therapy, Gemma still struggles with the condition. “For better or worse, it is has become a part of my life. It is an inescapable fact that I experience varying degrees of pain every time I engage in physical intimacy. I know there’s no such thing as 'normal' sex – but my pain feels isolating because it stems from a genital abnormality.”

But vaginismus is not an inevitable outcome for those with hymenal abnormalities and, even if someone does develop the condition, sex and relationship therapist Viv Howells notes that vaginismus “responds really well to therapy, external”.

Malformed hymens can carry physical risks as well as having psychological ramifications. Imperforate hymens, where the vaginal opening is completely covered, are most dangerous, as there is no way out for the period blood once menstruation begins. “The blood collects in the vagina, causing the vagina and uterus to enlarge as they fill with blood,” says Dr Overton. “This is called hematocolpos, external. There is no visible bleeding but the woman will have symptoms of monthly period pain. The enlarged vagina and uterus can cause pressure on the bladder, causing urinary frequency and pelvic discomfort.”

And attempting to correct an abnormality yourself risks “soreness, scarring, infection, bleeding and healing back together,” gynaecologist Dr Naomi Crouch warns, advising instead to arrange an assessment with a gynaecologist.

The phrase "Popping your cherry" can be a misleading image

Learning more about the variation in vaginas made me think about how little understanding many of us have of our own bodies. Growing up, I heard people use the phrase having your ‘cherry popped, external’ to talk about women having penetrative sex for the first time, but this image is totally misleading. Virginity isn’t always as simple as whether or not you've had penis-in-vagina sex, and people’s hymens aren’t a uniform sheet of material that are ‘popped’ by a penetrating penis.

In many cases, the hymen will stretch, external to accommodate a penis, rather than actually breaking, and, according to NHS guidance, external, some women bleed after having penetrative sex for the first time while others don’t. Dr Crouch also busts the myth that a hymen is only broken during sex (it can be broken through various other means, such as playing sport) and that the absence of a hymen means penetrative sex has occurred (it doesn’t).

A good way to deal with society’s often unsophisticated grasp of female sexual anatomy? “Get to know your own vagina!” says Viv Howells. “Just because it’s tucked away, don’t let it be a stranger - make friends with it!”

If more women did this, perhaps we’d have a greater understanding of our own bodies. If I’d had a closer look, I might never have ended up in A&E that night.

*Name has been changed

First published 5th April 2019