Hands-on science: Rubber Egg

Rubber Egg

Can you peel a raw egg and then make it bounce?

No? Liz Bonnin can. Join her as she demonstrates how to use membranes and osmosis to make a rubber egg.

Download the Rubber Egg PDF(595 Kb). Adobe Acrobat is required.

Step by step

Liz's video guide

In order to see this content you need to have both Javascript enabled and Flash installed. Visit BBC Webwise for full instructions

Liz Bonnin demonstrates how to remove the shell from a raw egg - and then make it bounce.

Checklist

| Difficulty: low | Just have to get past the thick scent of vinegar on your hands. |

| Time/effort: medium | Patience is a virtue- this requires three days to do well |

| Hazard level: low | Membrane eggs do break easily - handle gently and have a mop at the ready! |

You need

Eggs

Clear vinegar

Sealable container (reduces the smell)

Water

Food dye (any colour that takes your fancy)

What you do

Vinegar is poured over a raw egg.

Take two/three eggs and place them in a bowl or plastic container.

Pour vinegar in until the eggs are completely submerged.

At this point you will notice the egg is covered in little bubbles.

Leave for 72 hours.

Gently lift one of the (now rather delicate) eggs and gently rub away the shell.

The egg shell has nearly dissolved.

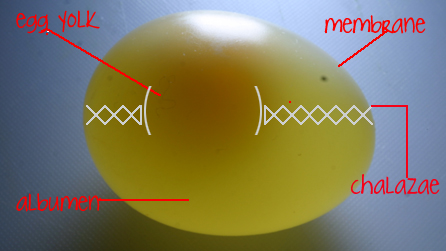

The shell should start to come away very easily. You will see a translucent sheath (membrane) underneath. Be careful, a mere nip, cut, or scratch can break the membrane and leave you not with egg on your face, but yolk all over your hands.

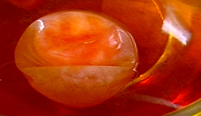

Spot the yolk in the membrane egg.

When all the shell is rubbed away, gently hold the egg under a dripping tap (if you turn the tap on too strong it will burst the egg). Then, hold the egg up to the light and admire your whole and translucent raw egg.

Now for the moment of truth: does your raw and shell-less egg bounce?

1,2,3 and bounce....

Hold it about 10-15cm above the ground or bench top and let go. The result is...

With a bouncing success, it's now time to utilise that special membrane and experiment with osmosis.

First up: take a tub of golden syrup and pour it into a bowl or container.

Carefully, place the membrane egg into the middle of the syrup.

Leave for at least one day (roughly 10 hours).

A very un-bouncy egg.

Has the egg shrivelled up? Does it look like a sorry excuse for an egg, let alone a bouncy and translucent one? Yes? Perfect.

Pick a colour to dye your egg. Take another bowl and fill it with tap water.

Squeeze about 10 drops of food dye into the bowl.

Take a spoon and very gently lift the egg out of the syrup and place it into the bowl of water/dye.

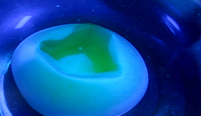

The deflated egg in blue water.

Leave for about six hours.

What should happen

Blue and bouncy.

The final stage should see you with a bulbous, bouncy, colourful - and let's not forget, completely raw - egg. You can shine a light through it with a torch and get a marbled effect or you can give it a bounce. Just take a lesson out of Liz's experience - and don't drop it from a tall work top!

If it doesn't work for you

There's no reason for this experiment not to work other than your egg hasn't been left in vinegar for long enough. After a few days press on the egg and if the shell is still hard, give it more time. At the three days point you should certainly see that parts of the shell have dissolved. Try gently scrubbing the rest away. If it's not coming off, put it back in the vinegar for another day.

Once you have a shell-less egg, the syrup and coloured water stages should not be a problem. The only error would come from accidentally tearing the membrane, but you'll know if you do this because, if nothing else, you'll be covered in yolk, or vinegar, or blue water, or all of the above.

What's going on?

An egg like never before

Pickled science

What did the vinegar do to the egg shell?

Vinegar is a weak acid (it is 5% acetic acid in water). Egg shell is made of calcium carbonate. When the two come together they create a chemical reaction that breaks down the calcium carbonate, and produces carbon dioxide (these are the bubbles we can see on the egg on the egg, in the film) After three days the shell is nearly all dissolved or is weak enough to be rubbed away. The result is a rubbery, translucent egg.

Membrane strength

The membrane is remarkable not just because it is semi-permeable but also because it is impressively tough. It actually contains keratin, which is found in human hair! This toughness explains why we can bounce (and not always burst) our rubber eggs.

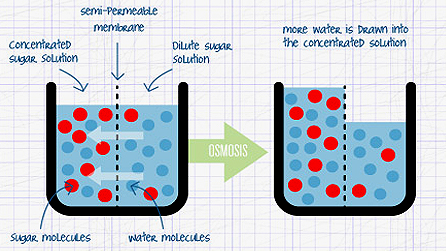

Osmosis ping-pong

As Liz explains so well in the video, osmosis is the movement of water from an area of low solute concentration (less things dissolved in the water) to an area of high solute concentration (more things dissolved in water), see the diagram above. Osmosis is really important because it takes place in every living cell in every living organism. It's how plants take up water from the soil, and how cells in our own bodies regulate themselves and don't burst or shrink when chemical processes are taking place.

Playing osmosis ping-pong has its advantages and so we utilised this bit of science not once but three times in our experiment.

Inflated egg

Firstly, the vinegar. Vinegar is largely water. The egg has a lot of proteins and fats dissolved in it. Of the two, vinegar most certainly has the lower solute concentration. This means that whilst the acid in the vinegar is breaking down the egg shell, more water is moving into the egg than is leaving it (as water is always travelling back and forth). This continues until the concentration levels of the egg and vinegar is pretty much equal. The result is a rather rotund little egg giving a new meaning to term 'water retention'.

Deflated egg

We used osmosis a second time in order to shrink the egg. For this we sought to reverse the osmosis gradient and force more water to leave the egg than enter it. For this we needed a solution with a solute concentration much greater than the egg. Enter the incredibly sugary substance that is golden syrup. So our once proud and bulbous egg will now, in less than half a day, deflate and shrivel, looking a little too poached for wear.

Blue and bouncy

The third and final bit of osmosis came from the coloured water. Obviously, being water, this solution is as dilute as we could hope for. The food dye doesn't affect the concentration at all, it merely acts as a marker for how the water is moving. A shrivelled egg with little water and the same amount of fats and proteins that it started with means there is no contest in the bid for low solute concentration. More water enters the egg, with blue dye dissolved in it, and voilà: Its bulbous. it's blue. It's bouncy. And it's still a raw egg.

Swot fact

If you wondered how the yolk always stays in the same place, despite changes to the rest of the egg, this is because of something called the 'chalazae'. Chalazae is modified albumen and acts a type of rope on either side of the yolk that holds it firmly in its place. See diagram above to get a better idea.

BBC iD

BBC iDBBC navigation

BBC links

BBC © 2014The BBC is not responsible for the content of external sites. Read more.

This page is best viewed in an up-to-date web browser with style sheets (CSS) enabled. While you will be able to view the content of this page in your current browser, you will not be able to get the full visual experience. Please consider upgrading your browser software or enabling style sheets (CSS) if you are able to do so.