Hands-on science: How to Investigate the Unknown

How to Investigate the Unknown

How do we know things?

Dr Yan uses canister rockets to demonstrate how you use the methods of science to investigate the unknown.

Step by step

Yan's video guide

In order to see this content you need to have both Javascript enabled and Flash installed. Visit BBC Webwise for full instructions

Why do some canister rockets fly higher than others? Dr Yan shows you how to answer all of your burning questions.

Checklist

| Difficulty: It's up to you | Start with something quick and easy to do - you'll end up repeating it many times! |

| Time/effort: medium | It takes time to carry out an experiment, but that's time well spent - you'll be rewarded with a deep understanding of what's going on. |

| Hazard level: low | Don't experiment with anything hazardous. The more you repeat it, the more likely something is to go wrong. |

It helps to have:

The burning desire to find something out!

The ability to observe carefully.

Trust in your own observations rather than other people’s explanations. As the scientific motto goes: "take nobody's word for it".

You need

Something that you can experiment with (a few suggestions are at the bottom of the page).

Predictions about what you expect to see.

Pen and paper to write down what you’ve done and the results you get.

A way of picking things in a random order (eg from a bag).

A way to analyse your results. This could be graphically (eg graph paper, or on a computer) or numerically (eg calculator, computer spreadsheet).

Catch up on Fizz Bang

This investigation is based on a previous Hands-on I made, called Fizz Bang.

Watch the Fizz Bang film and get inspired to delve into the world of canister rockets even further.

The Stages of an Experiment

Getting started

What do you want to know?

I want to investigate why some canister rockets take-off better than others.

Firstly, and most importantly, find something that you are really interested in.

Play around with it, and observe the results. I decided to use film canister rockets - I helped lots of people to set them off during the Bang Goes the Theory roadshows.

What often surprised them was that putting in loads of water and tablets gives a rubbish result. Furthermore, when adjusting the amounts to get the best launch it was difficult to predict the timing and height of the rockets. That made me realise that the details are quite complicated, and worthy of further investigation.

Think hard!

Make sure you take some time to think about what might explain what you've seen. Explain your ideas to other people and see if they have any more suggestions. It was talking to people at the roadshows that made me think hard about what the important factors might be in making the rockets go high.

Construct a hypothesis

I based my hypothesis on my observation and knowledge about how rockets work.

Your ideas can come together in what is called a 'hypothesis'. This is a potential explanation of what’s going on. It’s even better if you have several conflicting hypotheses, then you can plan experiments to help you decide between them.

You don’t have to believe all your hypotheses are necessarily right: a good experiment reveals which hypotheses are likely to be wrong. In fact, it’s often useful to also have a 'null hypothesis' - that nothing interesting is going on at all. If your experiment contradicts this null hypothesis, then that shows you’ve got something interesting to investigate.

Make some predictions

My hypothesis predicts that the space in the canister affects the rockets.

Think about how you can test your hypotheses. Come up with new predictions your hypotheses make. These should be falsifiable. This means that it’s possible to carry out an experiment which demonstrates the hypothesis is wrong (in science, it's never possible to completely prove that your hypothesis is right).

My predictions were:

1: That the amount of tablet in the canister has no effect on the height the rockets reach.

2: What does affect the height is the amount of space left in the container (after the tablet and water have been added) - too little space gives a poor launch, but so does too much.

If I find the largest amounts of tablet always give the highest rockets, it would falsify my main hypothesis, forcing me to think of alternatives.

Design your experiment

When designing your experiment, you use your predictions to help choose what variables to use. You then need to think about the three basic principles of experimental design: a) replication, b) control, and c) randomization.

Variables

Experiments usually have dependent and independent variables.

I estimated the height of the canister rockets using a modified tape against a wall.

The dependent variable is the thing you observe and record. It changes in response to the different things you vary during the experiment. In my case, the dependent variable is the height of the rocket. I measured this by sticking a long measuring tape to a wall outside. By taping coloured bars at every metre, and using the background lines of the bricks, I was able to estimate the rocket height easily.

I varied the 'amount of space' by dividing the canisters into sixths and pouring water in accordingly.

The independent variable(s) are the things you experimentally vary. I started with two independent variables: (1) the amount of tablet and (2) the amount of canister space. For the tablet amounts I chose to use a quarter, a half, or a whole tablet. For the amount of space, the canister divided easily into sixths, so I left empty one-sixth, two-sixths, three-sixths, four-sixths or five-sixths. Because I used three different canisters, I also decided to control for potential differences between them by treating the three canister colours as another variable.

a) Replication

The more replication, the more convincing any affects you see.

At the heart of any experiment is the idea of replication. Each result you get is a “data point”, and the more separate data points, the better the chance you have of spotting what’s happening.

The combination of each tablet amount with each ‘amount of space’, gave 15 possibilities. I repeated these on 3 different canisters, giving 45 tests to do, and 45 data points. That’s a good amount of replication to aim for!

b) Control

While doing your experiment, you should try to keep everything under careful control. Measure your independent variables carefully, and try to keep everything else the same. I used water from the same bottle, the same make of fizzy tablet, and launched the rockets from the middle of the same flat tile, wiping the previous water and tablets off before each new launch.

Sometimes, there are things you think might affect the experiment, but you can’t or don’t want to keep the same. For example, maybe you don’t have enough time to do your whole experiment on the same day, or maybe your experiment involves giving people a test, and you want to try testing different people. You can control for this sort of thing by including it as an extra variable.

I controlled for canister difference by using three canisters.

In my experiment, I did this for canisters. I didn’t use the same one all the time, in case I lost or damaged it, or accidentally picked a weirdly behaving canister. But I didn’t have enough canisters to use a separate one for each launch. So I controlled for differences between canisters by using 3 different ones, marked in different colours. I performed each combination of experimental treatments on each canister. I also made sure that the treatments were “balanced”: I didn’t, for example, use one tablet size or level of space more often with one particular canister - otherwise it would become tricky to tell which effects were due to the tablet and which to the canister.

Often, experiments also have special “control groups”, to see what would happen in the same situation but if no experimental manipulations were carried out. I didn’t need to do this, because I was pretty sure that the canisters wouldn’t take off at all unless there was some water and fizzy tablet inside!

c) Randomization

I randomised the order of my treatments by pulling a label out of bag.

You never quite know if there are other effects that might influence your experiment. You can stop these biasing your results by randomizing what you are doing. That way, unexpected influences (for example, the time of day) won’t affect one part of the experimental treatment more than another.

Here’s where a bag comes in handy. For example, I made sure I carried out all 45 rocket launches in a random order, by writing down the 45 combinations on 45 pieces of paper, putting them all into a bag, shaking it around, and pulling them out one-by-one. As an extra precaution, I also mixed up all my fizzy tablets and selected ones at random each time.

Carry out your experiment!

The more tests I did, the more I learnt about canister rocket flight.

It can take a while to do this! Setting up my experiment took 2 hours or so, and setting off 45 rockets took me at least 5 hours (I actually did about 60 rockets, as some had problems e.g. hitting the wall).

Don’t worry if it doesn't go as smoothly as you planned. Things rarely do...

Analyse the results

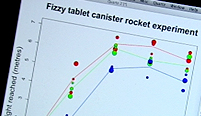

I plotted out my findings on an electronic graph.

There's a lot of ways you can examine your data - this is called 'statistical analysis'. The simplest way is to plot out what you recorded, as I did, but there’s also a whole area of mathematics that’s devoted to this!

When plotting, it’s usual to put the dependent variable down the side of the plot. Sticking to this convention helps other people grasp what’s going on. In this case I’ve put height of the rocket down the side (the “y-axis”). You can then use colours, symbols, and lines, as well as the distance along the bottom (the “x-axis”) to highlight the effects of the different independent variables.

Just plotting data like this reveals all sorts of patterns. For example, I could see almost immediately that the amount of tablet didn’t have any effect, because the bigger points in my plot (the bigger tablet sizes) weren’t consistently giving either higher or lower results.

If you have lots of data points, it can help summarising them into just a few values, for example, by taking averages. It can also help to give an idea of the range of your data. For example, the average height my canisters got to was 4.5 metres, but ranged from 35 centimetres to 7.1 metres(!)

However, summarizing all your data points into a few numbers like this risks losing useful information - like the vital fact that the height was massively influenced by the amount of space. A less drastic way of summarizing the information is to average together those points that you think show the same effect. For example, if you repeat the same test several times on the same person, you could use their average score. In my case, because I concluded that the tablet size didn’t make much of a difference, I plotted lines showing the height for levels of space and for different canisters, averaged over the 3 tablet sizes.

Things to look out for

Common problems with experiments

You usually encounter all sorts of practical problems when experimenting – the key is to give yourself lots of time. But there are some general problems that are often found when starting to design and carry out your own experiments:

Not enough replication – imagine you wanted to know whether it’s random whether toast falls butter side down or butter side up. You repeat the test 5 times, and it lands butter side up each time. Five identical results is a lot, but it’s still not enough to disprove the idea that it’s random. That’s because if it were random, there’s still a 1 in 16 chance of it either landing butter side up or butter side down 5 times in a row. By scientific convention, to disprove something, the chance has to be less than 1 in 20. In this case, you need at least 6 identical results. So you often need lots of data to produce a convincing result. In my experiment I collected 45 data points: that was about the minimum I thought I could get away with.

Experimenter bias – if you are hoping for a particular result, it’s easy to accidentally make your experiment give that result. For example, you might redo a result if it didn’t quite work as you expected, or if you are asking questions, you might subconsciously give away which answer you are expecting. All you can do is be scrupulous, randomize properly, and (if possible) carry out blind or double blind experiments (see What are 'blind' and 'double blind trials'? below).

Bad or no randomization – There are almost always going to be unknown influences on your experiment, and it’s unfortunately appealing to carry out your tests in a neat and tidy order. That’s why it’s important to force yourself to randomize. It’s also surprisingly difficult for humans to randomize properly. So picking out of a bag, tossing a coin, or getting a computer to give a random sequence, is a very good idea

Over-interpretation – When analyzing your data, it’s tempting to see patterns everywhere. But humans are notorious for seeing patterns and meaning, even in random data (such as the position of the stars, or the buttered toast example above). So you should be particularly careful when looking through your results and your plots.

What's going on?

What is Science?

How do we know things? The scientific answer is that we know things are likely to be true because they have been repeatedly tested. In fact, science is not a collection of facts or demonstrations. It is a tool for finding things out for yourself. That results in ideas that are convincing because they have been tested using evidence, rather than just taking someone’s word for it.

A lot of the world around you is unknown, and ripe for investigation. Even things you might think are well-known can benefit from careful scientific investigation. In fact, it’s only by testing and challenging ideas again and again that we can start to have confidence in them. For example, you shouldn’t necessarily believe the conclusions in my film: repeat my experiment yourself to try to prove me wrong, or see if you can take it even further.

How to test things

In science, you can prove beyond reasonable doubt that an idea is wrong - if it makes predictions that aren’t supported by the evidence. However, it turns out to be impossible to prove that a particular hypothesis is right - there could always be an alternative explanation you haven’t thought of.

The most famous scientific example is Newton’s theory of gravity. People thought it was correct for hundreds of years, until Einstein suggested a slightly alternative hypothesis. His “theory of general relativity” made testable predictions about how light is bent around massive objects. These predictions were famously confirmed in 1919 by observing starlight during a solar eclipse.

Einstein’s hypothesis wasn’t tested by an experimentally manipulating the starlight. But experiments, where you manipulate what’s going on, are much more powerful than simple observation. For a start, you can carefully control the conditions to get more repeatable results. More importantly, if you simply observe one thing happen followed by another, both could be caused by some other, unknown factor. If you deliberately experiment, you can argue that your results were specifically caused by your manipulations.

Your experimental predictions

Often, the key to an experiment is working out what predictions you can make - especially those that help you distinguish between competing hypotheses. In fact, in lots of science, just making the predictions is a whole subject in itself. For example, lots of climate science is based on making predictions from very complicated computer models.

When deciding what prediction to test, it’s easiest to focus on a single 'dependent variable' (or 'response'). In my case it was the height of the rocket. In other cases, it might just be a yes/no response (for instance, when testing toast dropping, did the toast land butter-side down?) In a medical trial it might be the change seen in the health or behaviour of a participant when they take the medication (or the placebo if they’re part of a control group).

Designing an experiment

The best experiments are designed quite carefully beforehand. They are usually very clear about their “null hypothesis” (what you expect to see if nothing interesting is going on). A common null hypothesis is that there is no difference between two things – for example the taste of red versus green peppers, the effectiveness of a new type of medical treatment versus the old one (or versus a placebo), or the buttered and non-buttered sides of a slice of toast.

Simple experiments often have just one “independent variable” (or “predictor”), but if you have time, it can help to have several, as I did. Not only does this mean you can test several things in one go, saving time and effort in the long run, but it can also allow you to spot if the two variables interact in an unpredictable way.

The idea of an “interaction” may need a little explanation. In my experiment, an example would be if the size of tablet was normally irrelevant, but did have an effect when the canister was (say) almost empty. I used what’s called a “crossed” design, where each level of space was tried with each size of tablet. That allowed me to spot these sort of subtle effects. I wouldn’t be able to spot them if I first tried changing the tablet amount, leaving the canister half full each time, then changed the space in the canister while keeping the tablet amount fixed.

If you do have a crossed design, you should also make sure that it is balanced: different values of each independent variable (eg a certain level of space with a certain tablet size) shouldn’t occur more commonly together, otherwise you risk confounding the effects of the two variables.

Control

There are many ways to use the idea of control and control groups when designing an experiment. One trick is when you are dealing with things that have inherent differences, such as individual people doing a test. You can test the same person 'before' and 'after' a particular treatment, then look at the difference. You’re essentially using their “before” score as a type of control, giving you an idea of how they would have scored without the treatment. That’s what I did for a Bang Goes The Theory programme, where I looked at the effect of listening to music on brain activity, testing people before and after they listened to music.

'Before' and 'after' testing has the problem that people usually get better at tests. In another study we did for the same programme, we instead contrasted two treatments - exercise and reading - testing people after each treatment. To ensure that people improving at the test didn’t bias our results, we randomized the order that the tests were given in. Sometimes people did exercise then reading, sometimes they did reading then exercise.

What are 'blind' and 'double blind' trials?

The problem of experimenter bias can be avoided by using blinding:

Blind trial

This is when the person taking the test does not have any information that tells them which test group they are in. If they were to know they might consciously or unconsciously act in a way that influences the outcome.

Double blinding

This is where neither the person taking the test nor the person administering the test knows who is in the control and who is in the test group. This means that the experimenter is unable consciously, or subconsciously to give the person taking the test any clues about what treatment they are receiving.

Randomisation

How does randomizing reduce unknown influences on your experiments? Well, in my canister experiment, imagine the seals on the canisters got weaker the more we popped them. What would happen if the order we tested wasn’t random, but we started with canisters almost full of water, and worked our way through until we ended on the almost-empty ones. Then the fuller canisters would have strong seals and go high, whereas the emptier ones would go low. These results might lead us to conclude the very opposite of what we should. Randomizing stops these sorts of problems.

If you are carrying out an experiment with a control group of separate subjects, it’s important that the people in the control group are picked at random. That’s what we did in our nationwide 'Brain Training' study – a computer made sure that volunteers were randomly given either a set of 'brain training' tasks, or a set of 'control' tasks (in this case, searching the internet for the same amount of time).

Analysis

Lots of analysis is based around trying to explain why your results vary. For example, the main reason why the height of my rockets varied seemed to be the differing amounts of space in the canister.

But even under exactly the same experimental setup, we might expect to see a little bit of variation in height. This is sometimes called the “error variation”, and understanding this is probably the major part of any statistical analysis.

So regardless of whether you actually end up doing complicated analysis of your results, you should try to give people not just single summary values of your results, but an idea of the amount by which those values vary.

What to do next

There’s no end to the experimenting you can do, and the depth to which you can take an investigation. Having narrowed down which hypotheses seem reasonable, you can then refine them and do further experiments.

For example, having seen my results, I’d like to see if I can use my knowledge of physics to make predictions about the shape of the curve, and look at more detail at the critical level of about 1/3rd empty space. The slow-motion shots of film canisters also make me think that the size and shape of the tablet might interfere with the water ejection, so I’d like to experiment with this, for example, by trying out fizzy powders (eg bicarbonate of soda plus vinegar).

Have a go!

Suggestions for things to test

Taste the difference

It’s surprising how important your expectations are in modifying your taste. Many people are convinced they can taste the difference between two similar foods, eg butter or margarine, red or green peppers, cheap or expensive brands. But often it’s not the taste they are going on. If people shut their eyes and aren't given any hints as to which of the two it is, can they still taste the difference? This is the sort of experiment that should ideally be done double-blind and randomised. For example, if you are testing one person, there should be two experimenters: one who randomly selects which of the two choices are given, who then passes them to the second experimenter, who has their eyes shut (or is blindfolded), and gives the test subject the food/drink.

Dependent variable: correct or incorrect identification of the food independent variables: you might not need any - it’s probably enough to test the null hypothesis that people’s guesses are essentially random. If you want to probe deeper, you could design an experiment where you lead people astray, for example by putting cheap food in an expensive packet.

Does toast tend to land butter side down?

If so, what might be responsible?

Dependent variable: which side the toast lands

Independent variables: how the toast is dropped (eg pushed off a table or held in a hand), height from which it is dropped, amount of butter, stiffness of bread/toast.

Methods for curing hiccups?

If you know someone who gets hiccups a lot, you could try a variety of suggested cures (eg holding breath, sudden shock, drinking from the back of a glass). In this case, it’s important to randomise the order that you try out the cures.

Dependent variable: cured or not, or length of time before hiccups stop

Independent variable: type of cure

BBC iD

BBC iDBBC navigation

BBC links

BBC © 2014The BBC is not responsible for the content of external sites. Read more.

This page is best viewed in an up-to-date web browser with style sheets (CSS) enabled. While you will be able to view the content of this page in your current browser, you will not be able to get the full visual experience. Please consider upgrading your browser software or enabling style sheets (CSS) if you are able to do so.