Dr Yan - the Thatcher illusion

Dr Yan on the Thatcher illusion

Illusions are fascinating because of what they reveal about how our brain works. This particular one, demonstrated to a Women's Institute meeting for Bang Goes The Theory, involves your perception of rotated pictures - usually faces.

Thatcherization

The numbers in square brackets refer to the notes and links at the bottom of the page - the sources that I've used for this article.

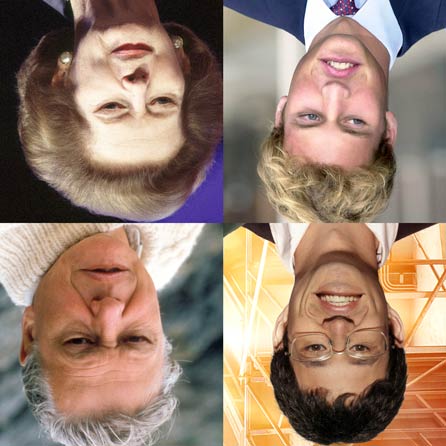

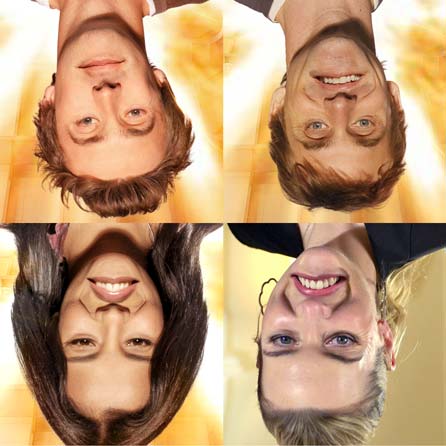

Most people can still recognise an image of a face that's been rotated upside-down, and they still do even when altered in rather major ways. In particular, a distortion known as 'Thatcherization' [1] often goes unnoticed - that's where the face is upside-down but the eyes and the mouth are changed to remain the right way up [2].

If the image is then rotated into the normal position, you're in for a shock as the face suddenly looks grotesque. Try rotating the line-up of suspects below - I’m particularly happy with how awful my own Thatcherized face suddenly becomes!

Spin me round

Click here to see the effect, or (even better) rotate your computer monitor if you can.

With photo manipulation programs, you can easily do the same to your own digital photos, but I've found some faces and expressions aren't so good.

Below are the other presenters, along with a face that definitely doesn't Thatcherize well. I suspect this is because the smile takes up a good portion of the lower part of the face, approaching the edges of her cheeks.

This problem (if having a great smile is a problem!) also seems to affect Liz's picture, but to a lesser extent.

You may or may not find these look strange, even upside-down. Most people find that the last one (Kate Winslet) looks odd upside-down, but much worse when rotated to the correct orientation - click here to see the effect.

Experiment yourself

What's great is that the illusion works well even when you know what's been done. That means you can try lots of experiments on yourself, your friends, and your family.

For example, if you have young children around, why not see if they spot the effect. Although it's been suggested that it may not work for children much under three years old [3], I’ve just found that it works on my daughter, aged two years and 10 months.

Or try gradually rotating a Thatcherized picture [4]. You’ll probably find that there’s a sudden point, at around 90°, when the face suddenly switches between grotesque and normal. You may find that the angle depends on several things, such as both the picture and the viewer.

It also seems to depend on whether you are rotating from normal to grotesque, or vice versa: the perception of grotesqueness seems to persist for longer than the perception of normality [5].

Some researchers have also found a much more gradual rotation effect. They showed people Thatcherized faces, rotated by a certain amount, then asked them to decide if they had been altered. The more upside-down the image, the less likely people were to detect the alteration [6].

What's going on?

The Thatcher illusion is fairly well studied in the science of visual perception. But like much in the brain, what’s going on is not fully understood. A few possible explanations have been suggested [7]:

Explanation 1

It's difficult for the brain to interpret expressions in upside-down faces. So we don't really recognise that the expression in an upside-down Thatcherized face has been altered at all.

The problem with this is that it's not really that difficult to work out upside-down expressions. The people in my first line-up have a variety of expressions, and it's easy to tell what they are.

Explanation 2

When looking at an object, our brains often have to work out which way up it is - to orientate it. To do this, we take into account both our personal expectations, independent of the object (eg which way up we are), and the details of the object itself.

For example, if we are sitting up, we expect the top of objects to be at the top of our visual field. If we then see a face with the forehead at the top, both our personal expectation and the orientation of the whole face agree.

Focusing then on a facial feature (say the lips), it's obvious which way up they should be - so a (right way round) Thatcherized face looks very wrong. But when the face is upside-down, our personal orientation and that of the face conflict, which makes it much less obvious which way up the lips should be, and so the Thatcherized face doesn't seem so odd.

Explanation 3

This relies on a well-established theory that there are two sorts of processing we do to recognise objects. One involves looking at the arrangement of features of the whole thing, and comparing this to a known mental map of such objects. The second involves closer inspection of individual, local features; in the case of a face: the nose, the mouth, the eyes, and so on.

For an upside-down face, we’re unlikely to have a known mental map, so we rely on looking at individual features. And the individual features of an upside-down Thatcherized picture look fine. It’s only when we see the face right way round that we can compare it to our idea of a normal face, and the picture looks horrible.

This explanation is backed up by the fact that recognising faces seems to be particularly reliant on the arrangement of facial features, with us gradually getting used to right-way-up faces as we grow up.

Moreover, this sort of recognition has been shown to particularly disrupted by rotation. It also explains the feeling that something separate kicks in as a Thatcherized face is rotated back to upright. But it implies that we can't just mentally rotate an entire face to work out the arrangement of features.

That's a bit odd, as we obviously don't have a problem rotating individual parts of the face: the smile on a normal (non-Thatcherized) face looks fine when the whole face is upside-down.

Just human faces?

It's worth pointing out that the illusion may not be specifically to do with faces, but with things that we are used to seeing one way up. On this note, experiments have been done with upside-down writing, and it's interesting that the effect also works (if more weakly) for pictures of women wearing bikinis [8].

If the upper and lower halves of the bikini are turned upside-down, it’s much less obvious when the entire picture is rotated. Of course, we see faces all the time, and bikinis quite rarely, so it's not surprising the 'bikini illusion' is weaker, but I've been quite convinced with the examples I've seen.

It may not be just humans either. Researchers have presented rhesus monkeys with faces of other, familiar monkeys that have been Thatcherized.

The Thatcherized monkey faces don't look too bad to humans, either way up, and they aren't that distracting to monkeys when shown upside-down, either. But they are distracting when shown right way up - a sort of monkey-Thatcher effect [9].

There have also been tests done on people who can't identify faces (but can recognise facial emotions) - a condition known as prosopagnosia.

Prosopagnosiacs are actually quicker at spotting upside-down Thatcherized faces. Indeed, as you gradually rotate a Thatcherized face until it is upside-down, they don't seem to have that switch that normal people have from instant spotting of the effect, to needing much longer to work it out [10].

There’s also a possibility that the impressiveness of the Thatcher illusion relies on several separate explanations. For example, recent research has highlighted the importance of an effect that we used to judge 3D. Faces are usually lit from above, and when the eyes and lips are upside-down, the reversal of shading makes them look particularly weird [11].

Further research

The explanations above seem a bit convoluted; my instinct is that they aren't phrased in a way that really captures the way the brain actually works - so I don't find them altogether satisfactory. However, it's possible that advances in our understanding of the brain will allow us to look at the neural pathways involved in the Thatcher illusion.

Coupled with recent research on how to get computers to recognise faces, I expect this to produce a much deeper understanding of the Thatcher illusion in the future. In fact, neurological research has already revealed something a little unexpected: it seems as though there are neurons that do detect something wrong with upside-down Thatcherized faces, but we just don’t consciously perceive it [12].

At Bang, we also intend to cover this illusion at bit more, so watch this space.

Notes and links

1. The Thatcher illusion, like so much of science, was accidentally discovered by someone experimenting for different reason. It's called this because psychologist Peter Thompson was distorting an easily available famous face (a left-over election campaign poster of Margaret Thatcher) in order to show his students a quite different visual effect.

The full details are described in 'The Thatcher illusion 28 years on...' (Perception, volume 38: pages 921–922).

2. Thompson P (1980) 'Margaret Thatcher: A new illusion' Perception, volume 9: pages 483–484

3. F Stürzel and L Spillmann (2000) 'Thatcher illusion: Dependence on angle of rotation' Perception, volume 29: pages 937–942

4. There's a great optical illusions website which has a rotatable online version of the original Thatcher image

5. F Stürzel and L Spillmann (2000) 'Thatcher illusion: Dependence on angle of rotation' Perception, volume 29: pages 937–942

6. J Lobmaier and F Mast (2007) 'The Thatcher illusion: Rotating the viewer instead of the picture' Perception, volume 36: pages 537–546

7. J Bartlett and J Searcy (1993) 'Inversion and Configuration of Faces' Cognitive Psychology, volume 25: pages 281–316

8. Anstis, S (2009) 'Mrs Thatcher and the Bikini Illusion' Perception, volume 38: pages 923–926

9. Adachi, I, Chou, D, Hampton, R (2009) 'Thatcher Effect in Monkeys Demonstrates Conservation of Face Perception across Primates' Current Biology, volume 19: pages 1270–1273. Also see the BBC news coverage

10. Carbon C-C, Grüter, T, Weber, J, Lueschow, A (2007) 'Faces as objects of non-expertise: Processing of thatcherised faces in congenital prosopagnosia' Perception, volume 36: pages 1635–1645

11. Talati Z, Rhodes, G, Jeffery, L (2010) 'Now You See It, Now You Don’t: Shedding Light on the Thatcher Illusion' Psychological Science, volume 21: pages 219–221

12. Carbon C-C, Schweinberger, S, Kaufmann, J, Ledera, H (2005) 'The Thatcher illusion seen by the brain: An event-related brain potentials study' Cognitive Brain Research, volume 24: pages 544–555

Brain Test Britain

Elsewhere on the BBC

Elsewhere on the web

Science speak

- Stephen Hawking, theoretical physicist (1942-present)

BBC iD

BBC iDBBC navigation

BBC links

BBC © 2014The BBC is not responsible for the content of external sites. Read more.

This page is best viewed in an up-to-date web browser with style sheets (CSS) enabled. While you will be able to view the content of this page in your current browser, you will not be able to get the full visual experience. Please consider upgrading your browser software or enabling style sheets (CSS) if you are able to do so.