Jem looks at fire pistons

Jem looks at fire pistons

Dr Yan recently demonstrated a fire piston to some suitably impressed onlookers, which you can watch online here. I thought I'd explain a little more how it works, and for those of you who enjoy maths, I've included my workings out too.

What's going on?

A fire piston works on the same principle as a diesel engine - compression ignition. I'm a big fan of this kind of thermodynamics as it matches well to the theory and is very repeatable.

Under pressure

Ignition occurs inside Dr Yan's fire piston

So what's going on inside a fire piston? To start with, the cylinder (tube) is full of air at normal room temperature and atmospheric pressure (18 degrees Celsius and 1 atmosphere).

When the piston is pushed down it squeezes the air in the tube into a much smaller space. You have to put in some energy to do this, and you end up with a smaller volume of hotter, higher pressure air.

Why? If you imagine the air as being made up of miniscule ping pong balls (molecules of gas) that whizz around and bang into things, then you can see that the more often and more energetically they bang into something the more of a push they can give, hence the higher the apparent air pressure.

Likewise, these more frequent energetic collisions can more readily pass on the air's heat energy, so the higher apparent temperature. You can see how doing some work on the air by squeezing all those molecules into a much smaller space can increase the pressure and temperature in that little space.

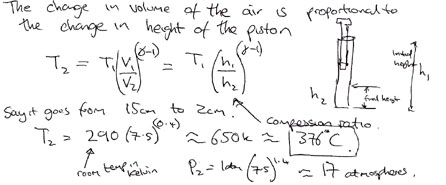

This is what's going on with Yan's fire piston. Once he's reduced the tube's volume to about a tenth of its previous size it increases the air temperature to well above that in an oven, and more importantly well above the ignition point of the cotton wool he's got in there.

Diesel engines

Now, back to diesel engines, which work on the same principle. Unlike a petrol engine a diesel engine has no spark plugs to initiate explosions in its cylinders. Instead, it compresses the air much more intensely (a volume reduction of about 20:1) causing a huge temperature rise.

Diesel fuel is then squirted into that hot air where it bursts into flame creating even more heat and pressure. This then forces the pistons back up at just the right time to push things round and power the car, boat or perhaps a generator.

Squeezing a gas with no heat transfer to its surroundings is called adiabatic compression. Here's the equation that describes what's going on - click here to see the full workings.

Anything else?

After messing about with fire pistons a few years back (I actually built one for my mum's Christmas present in 1995 - not sure if she used it much) I've often wondered if there may be another factor at play.

Most materials burn more readily if they're in a more oxygen rich environment. And when that air's compressed by the piston, although it's still 79% nitrogen and 21% oxygen, there is probably ten times more oxygen (and nitrogen) per cubic centimetre than there used to be. And this increase in available oxygen may also be what's helping combustion.

Just a thought.

Brain Test Britain

Elsewhere on the BBC

Elsewhere on the web

Science speak

- John Wheeler, theoretical physicist (1911-2008)

BBC iD

BBC iDBBC navigation

BBC links

BBC © 2014The BBC is not responsible for the content of external sites. Read more.

This page is best viewed in an up-to-date web browser with style sheets (CSS) enabled. While you will be able to view the content of this page in your current browser, you will not be able to get the full visual experience. Please consider upgrading your browser software or enabling style sheets (CSS) if you are able to do so.