| You are in: Health | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

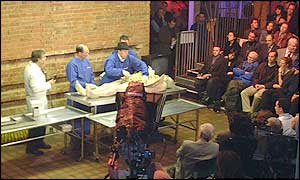

| Thursday, 21 November, 2002, 08:52 GMT Seat at the autopsy sideshow  Doctors, journalists and the public looked on

But there was no denying the drama of Britain's first public autopsy for 170 years on Wednesday night. After long queues delayed the public's entry into the Atlantis Gallery, in East London's Brick Lane, von Hagens finally arrived, characteristic trilby perched on his head, pushing the corpse of a 72-year-old German man.

But the attention to medical detail could not be denied. We were promised a cause of death and, after careful examination of all the organs, we were given one. Furthermore, the significance of pathology was frequently stressed, with special emphasis on the importance of the procedure to provide precise information to grieving loved ones. Only 3% of bodies in Britain now undergo an autopsy. First cut The surprising fact seemed to be that the subject had lived to the age of 72. He was an "unexceptional" man, we were told - apart, that is, from the fact that he had lost his job at the age of 50, become isolated from his family, smoked 60 cigarettes and drank two bottles of whisky a day, and died last March. Somewhere along the line he had also decided to offer his body to von Hagens for plastination. The first cuts were the hardest to fully absorb.

It was now that the police would intervene if the procedure was deemed to be illegal under the Anatomy Act, as the Queen's Inspector of Anatomy, Dr Jeremy Metters, had insisted it was. But the only movement from the gallery was from spectators covering their mouths and squinting with trepidation. Gradually the skin was teased away to reveal the subcutaneous tissue, which in turn was pulled back. There was barely time for people to fully appreciate that they were looking at an open human corpse before the thoracic shield - the bone sitting above the subcutaneous tissue - was whipped out, popped on to a tray and taken around the audience by one of the assistants. Tradition Bit by bit, organ by organ, the autopsy continued until the upper body was merely an empty cavity. Out came the heart, lungs and liver, and then, with the help of another pair of hands given its size and slipperiness, the abdominal block - including the intestines, kidneys, spleen and pancreas. With a little difficulty and the aid of a hacksaw, the brain was finally presented.

"Lay people are not able to view autopsies in universities or hospitals, therefore making it impossible for them to truly understand," we were told. The doctor reiterated that he was merely following in the tradition of the great Renaissance anatomist Andreas Vesalius, who educated the world with such procedures in the 16th century. The gallery was mostly filled with people of a medical background and journalists, though a number of laymen had come in the name of intrigue. "I think it's absolutely fascinating," said Louise Cotton, a 40-year-old accountant. "I've never seen anything like it before, it's just amazing." Cause of death With the organs removed, a proper examination could now be performed and the cause of death determined. One by one, the organs were dissected with something similar to a ham knife and commented on. The lung was inflamed, possibly as a result of chronic bronchitis suffered some time in the past, the heart and liver were probably a third bigger than usual specimens, there were multiple gall stones present, and there was a tumour in one of the kidneys.

Although alcohol is supposed to reduce the risk of hardening of the arteries, the man's heavy smoking had clearly taken its toll. With the spleen and prostate showing no signs of disease, the cause of death was straightforward. Given the size and colour of the heart and the swelling of one of the lungs, the man had clearly suffered from the failure of these two vital organs. The tumour in the kidney was written off as a not unexpected finding in a man of that age. Many, however, will remain unconvinced that such an event - and von Hagens calls his work "event anatomy" - was necessary to determine what had been such a predictable conclusion. By the doctor's own admission its primary role was to whip up public support against government plans to change legislation banning the importing of plastinates, which would make the Bodyworlds exhibition and this public autopsy the last of their kind in Britain. Von Hagens will undoubtedly find it harder to convince the wider public of his methods than those who witnessed the autopsy. Was it education, as he insisted, or plain sensation? Most will see it as the latter. | See also: 21 Nov 02 | Health 20 Nov 02 | Health 20 Nov 02 | Health 20 Nov 02 | Health 20 Nov 02 | Health 10 Feb 01 | PM Internet links: The BBC is not responsible for the content of external internet sites Top Health stories now: Links to more Health stories are at the foot of the page. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Links to more Health stories |

| ||

| ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------- To BBC Sport>> | To BBC Weather>> | To BBC World Service>> ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------- © MMIII | News Sources | Privacy |